È questa la prima parte di una serie di tre dedicata all’incredibile storia di Josephine Howard (vero nome, Gertrude Wilkins), un’attricetta teatrale che visse una vita particolarmente intensa nei soli 29 anni della sua breve esistenza. Sebbene la sua personalità rimanga un po’ sfuggente, ella incrociò una straordinaria serie di persone le cui vicende sembrano uscite da un romanzo. È un racconto contorto che dai vertici della celebrità della rivista newyorkese ed europea porta ad un emaciato cadavere devastato dalla droga in un albergaccio di Broadway, con un contorno di truffatori, gangster, avventuriere e ballerine disperate, oltre a tre suicidi. In questo post, ripercorro gli esordi di Gertrude Wilkins e quelli del suo primo marito, il tormentato ballerino Jack Jarrott, risucchiato dalla sua grave tossicodipendenza in una tragica, straziante spirale discendente che lo portò a morire, povero e anonimo, nel 1938.

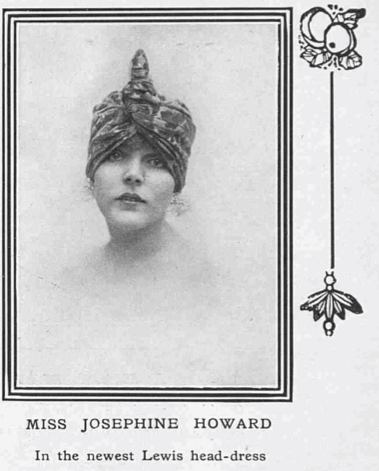

“Fashionable Creations by Notable Artists in the World of Dress,” The Tatler, June 25, 1913, p. xvi

“Fashionable Creations by Notable Artists in the World of Dress,” The Tatler, June 25, 1913, p. xvi

The entertainment business is the stomping ground of fabulists, but this is the story of a group of people particularly adept at the art of self-creation. We tend to forget how easy it was in the first few decades of the 20th century to reinvent oneself at will, with no pesky fact-checkers to lift the covers off rampant fabrications, and of course the press was in on the game, happily shoveling stories constructed out of diamond dust and blarney. What follows could easily have come from the pages of a James Ellroy novel were Ellroy to shift his attention back a few decades, and while there’s no full-out murder here (at least, I haven’t stumbled upon one), there is practically everything else. It’s a convoluted tale that moves from the heights of celebrity in New York and European revues to an emaciated, drug-ravaged corpse in a Broadway flop house; it includes fraudsters, gangsters, gold diggers and desperate chorines as well as three suicides, one of which was accompanied by a note written in a champagne-soaked haze that ranks as the most bizarre farewell letter I’ve ever read. Tying it all together is Josephine Howard, the stage name of Gertrude Wilkins of Jersey City, New Jersey, and while her personality remains frustratingly incomplete in comparison to the men in her life, it’s possible to piece together a psychological profile made more beguiling by the irresistible pull of conjecture.

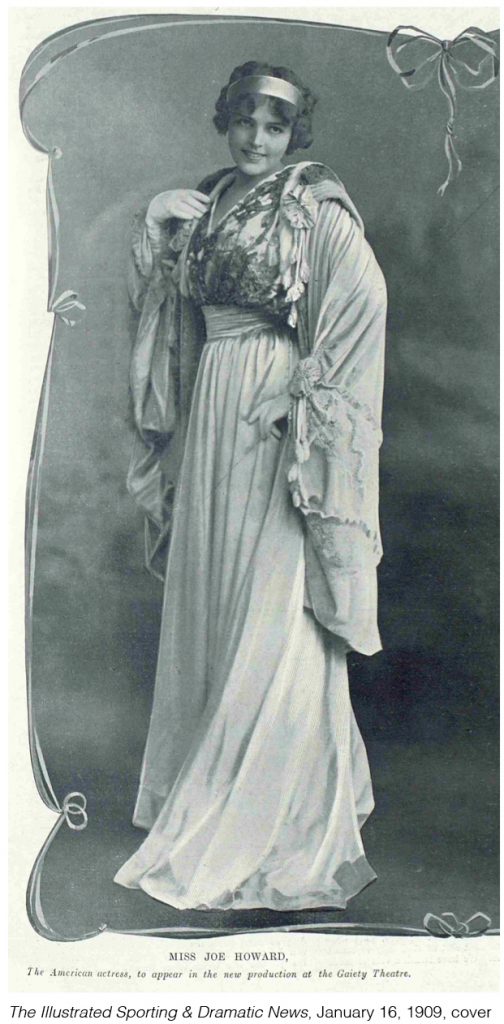

I’d never heard of Josephine Howard when my eyes fell on the October 1918 Variety notice, “Josephine Howard, formerly of ‘The Follies,’ and who has appeared in London, died in Toronto of influenza.”[1] Being relatively well-versed in the Ziegfeld Follies, I was surprised to find a name I didn’t recognize, and she wasn’t in the index of any Follies book or website, so naturally my curiosity was piqued. It took some time and plenty of creative research to piece her story together, and more remains to be done, but it’s fair to say she packed an awful lot into the final nine years of her life. She was born in 1889, the daughter of a New Jersey fireman, but it’s not until she was 19 and already in London that I’ve found a concrete reference, when she appeared in a small role at the Gaiety Theatre in Our Miss Gibbs, billed as Joe Howard. That was in January 1909, when she made the cover of The Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News, but she was back in New York by the end of that year, and while she’d frequently return to London, I’ve been unable to discover any further British stage credits.[2]

I’d never heard of Josephine Howard when my eyes fell on the October 1918 Variety notice, “Josephine Howard, formerly of ‘The Follies,’ and who has appeared in London, died in Toronto of influenza.”[1] Being relatively well-versed in the Ziegfeld Follies, I was surprised to find a name I didn’t recognize, and she wasn’t in the index of any Follies book or website, so naturally my curiosity was piqued. It took some time and plenty of creative research to piece her story together, and more remains to be done, but it’s fair to say she packed an awful lot into the final nine years of her life. She was born in 1889, the daughter of a New Jersey fireman, but it’s not until she was 19 and already in London that I’ve found a concrete reference, when she appeared in a small role at the Gaiety Theatre in Our Miss Gibbs, billed as Joe Howard. That was in January 1909, when she made the cover of The Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News, but she was back in New York by the end of that year, and while she’d frequently return to London, I’ve been unable to discover any further British stage credits.[2]

Whether or not Gertrude learned stagecraft at the Gaiety, she clearly developed a keen appreciation of how a tall blonde beauty like herself could get by without any obvious source of income. How else can we interpret an article from December 1909 reporting she was robbed of diamonds and gold when her bulldog Topsey was snatched during a walk in Central Park? The jewels, the twenty-year-old claimed, were set in Topsey’s teeth, placed there as a gift from her admirer, the Hon. Chester Ashburton, “a distinguished club and society man of London.” Needless to say, there was no Chester among the barons Ashburton, and the journalist obviously took the whole story with a pinch of salt, reporting that the dog-nappers “wore dark slouch hats, and might have been thieves or actors.” He did however mention her “sumptuous apartments” on Central Park West, and quoted Josephine’s explanation for her pooch’s sparkling gnashers: “rather than offend me by sending jewels in the conventional way, he took advantage of my well-known love of dogs and had the gems set in Topsey’s teeth.” The dog was returned, minus his valuable molars.[3]

The article just happened to mention her hopes for a good part in the upcoming Broadway show The Arcadians, an extremely successful musical brought over from London by Charles Frohman (she was not in the English production) which was in tryouts that same month. She was cast, but it was a small role, like all the roles in her very brief career as Josephine Howard, and if her Follies claims are true, it means she left The Arcadians before the end of the run and joined the Follies of 1910 in a part so tiny she doesn’t get mentioned anywhere. In fact I doubted she ever was under Ziegfeld’s umbrella, but a 1911 article in the New York Times about a lawsuit she won against horse dealers says she was in the 1910 company, and given the proximity of dates there’s every possibility the claim is true. However, the Follies had a rigid caste system in place for its “girls,” with showgirls at the top, then dancers, then the extras, so Wilkins’ self-promotion as a Follies girl was, shall we say, disingenuous.[4]

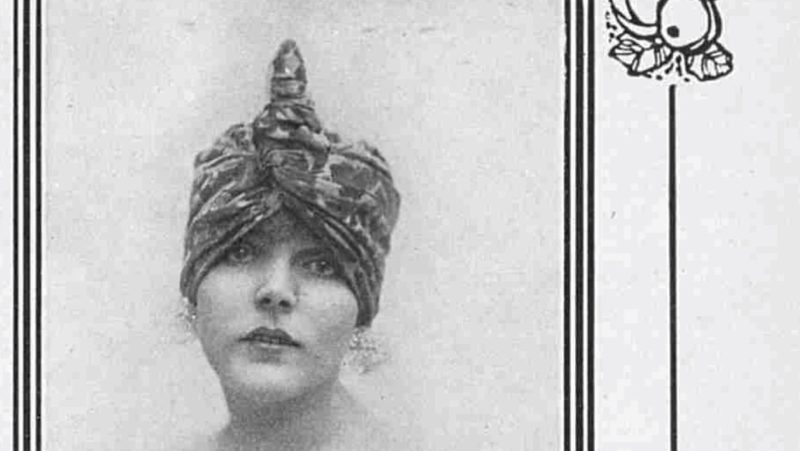

Gertrude crossed the Atlantic on luxury liners like the Lusitania several times in the next couple of years, her bills no doubt paid by more pragmatic exemplars of the Hon. Chester Ashburton School of Sugar Daddies. Her association with that august and storied institution may have been advanced through her friendship with Mary Jane Cleveland Van Rensimer Barnes Creel, a former waitress from eastern Pennsylvania with no right to use either Barnes or Creel in her name, but Mary Jane was never fussed by legal fine points. In December 1912 she was front page fodder for newspapers worldwide when, in her luxury Parisian flat, she pumped two bullets into her lover Walther de Mumm, of the champagne family, and then disappeared with her cook and maid (of course I plan on returning to Van Rensimer at a future date).[5] Six months later de Mumm was marrying a Kansas beauty and, sensing a publicity opportunity, Gertrude suddenly popped up telling journalists she’d raced from London to Paris because her dear friend Mary Jane was suicidal over her ex’s betrothal. On the same page that the papers reported on the champagne king’s wedding and Josephine Howard’s selfless proof of friendship, were interviews with Van Rensimer herself assuring everyone she was completely over her mad infatuation and never had any intention of harming herself. For both women, notoriety was just a more vulgar word for self-promotion, and no doubt they enjoyed seeing their names back in newsprint.[6] That summer of 1913 was an especially eventful one for Gertrude, not just for the Paris mission of mercy and the photo of her in a fetching turban by Maison Lewis that appeared in The Tatler, reproduced at the top here, but because that’s when she met her first husband, the dancer Jack Jarrott.

JACK JARROTT

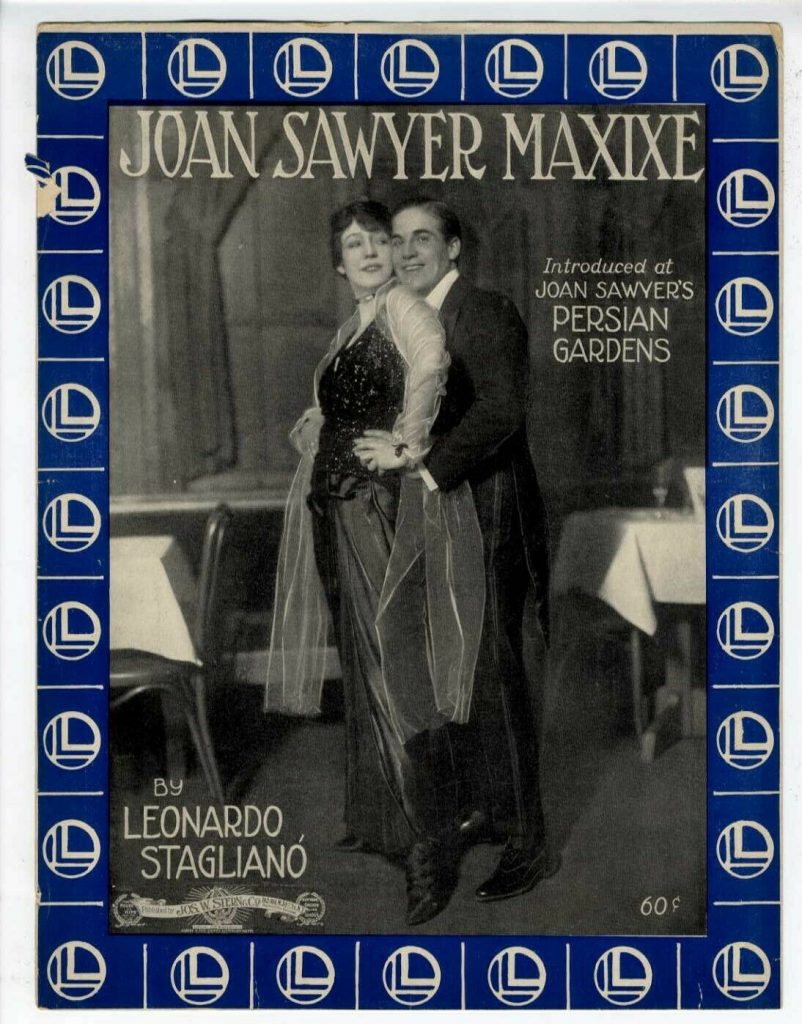

Joan Sawyer and Jack Jarrott, 1914

Welcome to my current obsession. If you were someone living in the teens and even only vaguely aware of the dance craze sweeping the U.S. and Europe, you would have been familiar with John W. (Jack) Jarrott. Around the time Vernon Castle was scaling the heights of exhibition ballroom dancing, Jarrott was receiving glowing reviews, popularizing ragtime dancing among white audiences and making the Grizzly Bear, the Turkey Trot, the Maxixe and other permutations all the rage. He performed with African-American bands in Chicago dives and the Palace theatres of New York and London, partnered Joan Sawyer, Vera Maxwell and, very briefly, Mae Murray, and appeared in the 1916 feature The Scarlet Road. Yet when his lifeless malnourished body was found in 1938, consumed by decades of drug addiction, it lay unclaimed at Bellevue Hospital’s morgue for two days before someone from the National Vaudeville Artists Association found out and gave him a decent burial. I can’t begin to fathom the demons Jarrott was struggling with, but I do know his very messy, ultimately tragic life deserves to be told in a more generous manner than was accorded by the moralistic obituaries. He wasn’t the only unstable man Gertrude Wilkins got involved with, but he was the most fascinating.

Jack’s earliest years are a mystery, not helped by his tendency to make things up on official documents. His death certificate says he was born September 2, 1887 (probable), but his draft card lists 1885, with the recruiting officer’s unusual handwritten note: “he could not state with certainty the year of his birth, but claimed he had completed his thirtieth year.” It’s likely he was stoned at the time, so we can’t be sure whether to give credence to the other information, like Macon, Georgia as his birthplace. On a ship manifest he put Dallas, Texas (also mentioned in a 1914 article), and a couple of his obituaries said he was from Jacksonville, Florida; one of them wrote that his father was a gambler killed in a casino and his mother ran a roadhouse, but I’ve been unable to find any corroborating evidence; more digging is needed.[7]

His earliest credited role was as the Bell Boy in George M. Cohan’s show The Yankee Prince, which opened in New York in April 1908, then moved to Chicago later that year and was still touring the U.S. in early 1909.[8] When it was over, it appears he returned to Chicago and there got involved with some very shady characters while also entering into the African-American music and dance scene in that city’s most notorious locales. Details are vague, and in many sources misinformation has been frustratingly perpetuated, but here’s what we can say for certain: around this time Jack began performing in some of the infamous saloons owned or operated by Roy Jones, one of Chicago’s truly sleazy crime kings with hands in white slavery, underage prostitution, narcotics and every kind of criminal activity imaginable. What makes Jones interesting for us is that his establishments hosted mixed groups of blacks and whites, including prostitutes as well as entertainers. Among the latter group were “Bricktop” Smith and Wilbur C. Sweatman, both soon to be major names in jazz and ragtime; “Bricktop” later recalled that Jones’ back room was “one of the best in Chicago.” I can’t say for certain that Jack performed at the same time as these future stars, but Variety reported that he’d been “for a long time the principal attraction at Roy Jones’ Amusement Café.” This would have been sometime between 1909 and summer 1911, so definitely around the same period as Sweatman.[9]

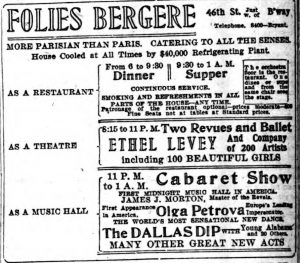

This was the moment when the Grizzly Bear dance became a cultural phenomenon, and whether originated in Chicago’s Levee District or simply popularized there, the “Grizzly” quickly became so much a source of contention for the way the dancers closely held each other that it was banned in the Windy City even while sweeping the country. Some secondary sources claim that Jarrott introduced the Turkey Trot and the Grizzly Bear to the world with Louise Greuning, but the information is suspect and I’ve not found any reference to a Louise Greuning.[10] What’s more, “Dago Frank” Lewis, another crime boss who also ran a brothel-cum-saloon, claimed at the time that his place was where the dance originated.[11] In the end, we should be less concerned with where it started than with how it started, most likely among black entertainers and then disseminated by white dancers like Jarrott who picked it up in Chicago’s dives. Jack took those influences with him when he burst on the cabaret scene billed as “Young Alabama” performing a Grizzly variant, the “Dallas Dip,” at New York’s recently opened Folies Bergere.

The New York Herald, June 25, 1911, section 3, p. 5. Note that future star Olga Petrova was making her U.S. debut at the Folies Bergere.

“Ninety per cent of all the ‘rag’ dancers in New York look foolish, after seeing Young Alabama,” exclaimed Variety’s Sime Silverman, who led a chorus of critics heaping praise on Jarrott’s footwork. “He is the slickest of the shoulder-and-foot-dancers. An easy grace and a dandy personality make him a certainty” wrote Variety’s “Dash,” mirroring his colleague in praising Jarrott’s dancing: “Alabama makes a pretty rag two-step of his work, moves over the stage quickly, intermingles some neat whirlwind work, and makes a great big hit with the audience.” Almost immediately, photos of Jarrott and his dance partner Bena Hoffman (1883-1921) appeared in syndicated newspaper columns nationwide, furthering the dance’s fashionableness while winking at its hints of impropriety. Ruth St. Denis was doing a vaudeville number at Hammerstein’s at the same time, leading an unconvinced “Dash” to compare the two: “My, Oh, My! you should see ‘Young Alabama’ at the Folies Bergere for a ‘Grizzly.’ That’s the stuff. In a theatre with a stage at either end with Ruth St. Denis on one and Young Alabama on the other you would never look at the exponent of the classical in body contortions and arm movements.”[12]

Why the nickname Young Alabama (or briefly, the Alabama Kid)? Silverman objected to it, saying audiences would think Jarrott was a black performer, suggesting the public assumed dancers from the Deep South would be African-American.[13] I suspect that was exactly what Jack wanted, to draw attention to the ties that linked his moves with ones he would have seen in places like Roy Jones’. In any event he took heed of the advice and soon reverted to his own name in vaudeville and cabaret, but it was mostly small stuff or understudy parts until March 1913 when he was engaged by British actor-producer Seymour Hicks to partner Follies star Vera Maxwell (1891-1950) on a European tour.

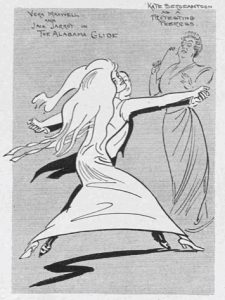

I mentioned Maxwell briefly in my previous post, referring to a supposed insurance policy taken out on her feet. She’d been a favourite dancer and then showgirl with Ziegfeld who “burst upon the Broadway scene with what we would call today the force of an explosion measured in megatrons.”[14] It’s unclear whether it was Maxwell herself or Hicks who suggested Jarrott as her partner, but the following month the two were in London dancing the Alabama Glide among other numbers in the musical revue All the Winners at the Empire; the act proved so popular that their engagement was extended through the summer.[15]

“Our Captious Critic at the Empire,” The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, June 7, 1913, p. 681.

“Our Captious Critic at the Empire,” The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, June 7, 1913, p. 681.

The show’s success, combined with the public’s continued hunger for all things dance related, led Cecil Hepworth to produce a short film of Jarrott and Maxwell in May called Always Gay, in which they danced the “Evening News Waltz no. 3” with composer Archibald Joyce also on screen conducting his own melody. The short, which appears to be lost, played throughout the British Isles in June,[16] which may have been approximately the time Jack met our friend Gertrude Wilkins in London. Actually, I could be wrong about that – this is pure conjecture, but I have a feeling theirs was a whirlwind courtship, so perhaps they’d known each other for only a very brief period of time when they got hitched sometime in early August. Variety learned the news over a week late,[17] which makes me wonder: Gertrude ate up publicity, so could it be that Jack knew it was a mistake pretty soon after the vows were said, and tried to keep the whole thing quiet? Again, this is complete guesswork on my part, but given how unsuitable they were to each other, it’s not beyond the realm of probability.

When Jarrott and Maxwell travelled to Berlin for a gig at the Wintergarten,[18] Gertrude followed her husband, and in October the three had an adventurous voyage back to New York when their ship, the Großer Kurfürst from Bremen, came to the rescue of the S.S. Volturno, a passenger ship engulfed in flames in the middle of the North Atlantic. Dramatic photographs Jack took from their ship appeared in North American newspapers; the trio assisted the rescued women and children as much as possible through the night, so much so that Wilkins was hospitalized once back in port for scarlet fever, believed to have been contracted from a child who was ill. Though hardly a noted personality and with barely any credits to her name, Gertrude (as “musical comedy actress Josephine Howard”) managed to get articles placed in the papers about her selflessness in the face of tragedy and her subsequent hospitalization.[19]

The following month Jack got a surprise when Maxwell announced she was partnering with another dancer – if there was any bad blood between the two, it disappeared in 1915 when they reteamed – and he started talks with Mae Murray to do a vaudeville act together, but that didn’t pan out for another year. Instead he joined the Chicago company of the musical The Doll Girl and was welcomed back to his old stomping grounds: “Mr. Jarrott, it is said, has his dancing source in the cabarets of this vicinity, and he returns graced with the wreaths of victory won in conquests on the dancing fields of Europe. At any rate, he is quite the most easily observed of the tangoists I have encountered…”. Jack’s temper, however, got him into trouble for the first time publicly when a spat with the valet of the show’s star, Richard Carle, led him to resign. Perhaps it wasn’t such a bad thing, because 1914 turned out to be the best year of his professional life.[20]

In Part II, I’ll be tracing Jarrott’s continued rise, together with a significant detour into the life of Joan Sawyer, containing quite a bit of new information.

Jay

Big thanks for help with this post go to Laurie Sanderson and the Ziegfeld Club, Sally Sommer, Bryony Dixon, Oliver Hanley and Frank Dabell.

[1] “Epidemic Casualties,” Variety, Oct. 18, 1918, p. 5.

[2] J.P. Wearing, The London Stage 1900-1909: A Calendar of Productions, Performers and Personnel (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014), p. 48; The Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News, January 16, 1909.

[3] “Actors or Thieves?,” Los Angeles Daily Times, December 13, 1909, p. 2.

[4] “News of Plays and Players,” The Sun, December 8, 1909, p. 9; “American Premiere of The Arcadians,” The Billboard, January 8, 1910, p. 5; “The Liberty Theatre. ‘The Arcadians’,” New-York Daily Tribune, January 18, 1910, p. 7; “Durland Company Loses,” The New York Times, April 26, 1911, p. 7.

[5] Practically every newspaper in France, the UK and the US between December 14 and 16, 1912 carried news of the de Mumm shooting. For the essentials, see: Jean Lévèque, “Le drame du jour. C’étaient deux amants…,” Gil Blas, December 14, 1912, p. 1; “Le drame de la rue des Belles-Feuilles,” Le Petit Journal, December 15, 1912, p. 1; “Le drame de Passy. Qui a tiré le premier ?,” L’Intransigeant, December 16, 1912, p. 1; “De Mumm Puts Blame on Woman, The Sun [New York], December 15, 1912, pp. 1-2; “De Mumm Shot by American Woman After He Had Kicked Her,” The New-York Tribune, December 15, 1912, pp. 1, 4.

[6] “Mumm Fears to Wed After Suicide Hint,” St. Louis Star, June 3, 1913, p. 3; “De Mumm, Shot by Mrs. Barnes, Wed in London,” The World [Evening Edition, New York], June 3, 1913, p. 1; “Mrs. Barnes Threatens Suicide,” The Sun [Baltimore], June 4, 1913, p. 2; “Widow Has Forgotten DeMumm,” Lincoln Daily News, June 3, 1913, p. 6.

[7] Information from the death certificate was viewed at https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=61778&h=248375&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=fUb816&_phstart=successSource;

Draft Registration Card for John W. Jarrott, June 8, 1917, https://www.ancestry.com/interactive/6482/005264778_03841?pid=1503493&treeid=&personid=&rc=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=fUb814&_phstart=successSource; Ship manifest, Großer Kurfürst departing October 4, 1913 from Bremen to New York: https://www.libertyellisfoundation.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiMTAwNzcwMDEwMDQxIjs=/czo4OiJtYW5pZmVzdCI7; “Attractions at the Theaters,” The Boston Sunday Globe, May 17, 1914, p. 44; Annie Oakley, “The Theatre and Its People,” The Windsor Daily Star, June 25, 1938, section 3, p. 4.

[8] “New Play at Hartford,” The New York Daily Tribune, April 3, 1908, p. 7; Chicago Public Library Digital Collections, Chicago Theater Collection-Historic Programs, Colonial Theatre, Yankee Prince (October 4, 1908), https://cdm16818.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/CPB01/id/5850/rec/1; “Plays for This Week,” The Illustrated Buffalo Express, January 17, 1909, p. 29.

[9] “Chicago,” Variety, April 27, 1912, p. 20. Jones’ name appears frequently in Chicago papers of the era and forms part of nearly every book about the city’s crime bosses of the era. For examples, see “Wayman Promises to Reveal Workings of Giant ‘Vice’ Trust,” The Inter Ocean, April 27, 1909, p. 1; “Raid Levee and Cabarets for Witnesses,” The Chicago Daily Tribune, April 12, 1913, p. 1. Also, Cynthia M. Blair, I’ve Got to Make My Livin’: Black Women’s Sex Work in Turn-of-the-Century Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), pp. 141, 271; Mark Berresford, That’s got ‘em!: The Life and Music of Wilbur C. Sweatman (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), pp. 61-62; Jan Voogd, “‛A Case of Peculiar and Unusual Interest.’ The Egg Inspectors Union, the AFL, and the British Ministry of Food Confront ‘Negro Girl’ Egg Candlers,” in Jennifer Helgren, Colleen A. Vasconcellos, ed., Girlhood: A Global History (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010), p. 128. However, significantly more work needs to be done on the dancers who appeared in the saloons.

[10] The two main secondary sources for information on Jarrott are riddled with errors. Both Barbara Naomi Cohen-Stratyner, Biographical Dictionary of Dance (New York: Schirmer Books, 1982), pp. 457-459 and Julie Malnig, Dancing Till Dawn: A Century of Exhibition Ballroom Dance (New York: Greenwood Press, 1992), p. 27, give incorrect dates for Jarrott and claim that he began his career performing in theatricalized boxing matches before dancing in clubs owned by August Reilley (or Reiley), including the “Ray Jones Café,” where he and Louise Greuning originated the Turkey Trot and the Grizzly Bear. To begin with, the so-called owner was August Riley, and it was Roy Jones, not Ray; what’s more, Jones seems to have owned his own establishments. (“Roy Jones Sells His Resort,” The Chicago Daily Tribune, April 24, 1914, p. 11.) In addition, I can’t find any Louise Greuning. Frustratingly Wikipedia and other websites have perpetuated these mistakes and complicated them further by spelling the latter’s name Gruenning.

[11] “Dago” remains an offensive if old-fashioned word in the U.S. connoting people of Italian origin. “‛Dago Frank’ is Defying Police,” The Chicago Daily Tribune, April 29, 1911, p. 3; “‛Grizzly Bear’ Danced in Cafes, Says Report; Closed,” The Inter Ocean [Chicago], May 1, 1911; “Levee Opens Up; Spotters Watch,” The Chicago Daily Tribune, November 30, 1911, p. 2.

[12] Sime, “‛Folies Bergere Dancers,’ with Young Alabama and Rena [Bena] Hoffman,” Variety, August 5, 1911, p. 20, in which Silverman says that Jarrott was discovered in Chicago by theatre producer Henry B. Harris. Dash, “American Roof,” Variety, September 16, 1911, p. 20; “Have you Danced the Daring ‘Dallas Dip’?”, San Francisco Chronicle, July 16, 1911, Sunday Magazine; Dash, “Hammerstein’s,” Variety, August 5, 1911, p. 22. See also “News of the Theatres,” The Sun [New York], June 25, 1911, section 3, p. 5.

[13] Sime, op. cit., p. 20.

[14] Marjorie Farnsworth, The Ziegfeld Follies (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1956), p. 52. Farnsworth discusses Maxwell in several evocative pages that truly bring her to life.

[15] “Vera Maxwell for London,” March 21, 1913, Variety, p. 10; “‛All the Winners’ – the Winning Revue at the Empire Theatre,” The Tatler, April 23, 1913, p. 101; “Hicks Picked Good Ones,” Variety, April 25, 1913, p. 4.

[16] “Kinematograph Notes,” The Stage, May 29, 1913, p. 28; Advertisement, The Express, June 7, 1913; Stephen Bottomore, “Selsior Dancing Films, 1912-1917,” in Julie Brown, Annette Davison, eds., The Sounds of the Silents in Britain (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 169.

[17] “London,” Variety, August 15, 1913, p. 17.

[18] “Die neue Spielzeit im Wintergarten,” Berliner Börsen-Zeitung (Morning Edition), September 5, 1913, p. 6; “Vergnügungschronik. Wintergarten,” Berliner Volkszeitung (Morning Edition), September 14, 1913, p. 3.

[19] “Remarkable Photographs Picturing Volturno Horrors,” The Evening World [New York], October 15, 1913, p. 3; “Volturno Afire, Survivors Arriving at Rescue Ship and Passengers Who Cared for Them,” The Edmonton Journal, October 25, 1913, p. 9. The latter has a photo of Maxwell and Wilkins (with the latter’s dog) on the Großer Kurfürst deck, but it’s too blurry to reproduce. Jarrott’s photos also made it into Popular Mechanics, December 1913, pp. 808-811, but without his credit and copyrighted to Underwood & Underwood. “Actress, Heroine of Volturno, Ill,” The Thrice-A-Week World [New York], October 29, 1913, p. 3; “Sea Waifs Gave Actress Scarlet Fever,” The Kansas City Star, October 29, 1913, p. 6A.

[20] “A Pair of Dancers,” Variety, November 7, 1913, p. 3; Percy Hammond, “Refreshing Musical Show at the Studebaker,” The Chicago Tribune, December 15, 1913, p. 14; “Jarrott Quits ‘The Doll Girl’,” The New York Clipper, January 17, 1914, p. 19.

English

English

Cracking story, Jay. Just goes to prove that life was no less interesting or racy back in those far off days….. I recall interviewing a World War One veteran in his mid 90s in the early 1990s) who told plenty of very daring post-War stories about dance hall girls etc in Coventry in the period 1919-20.