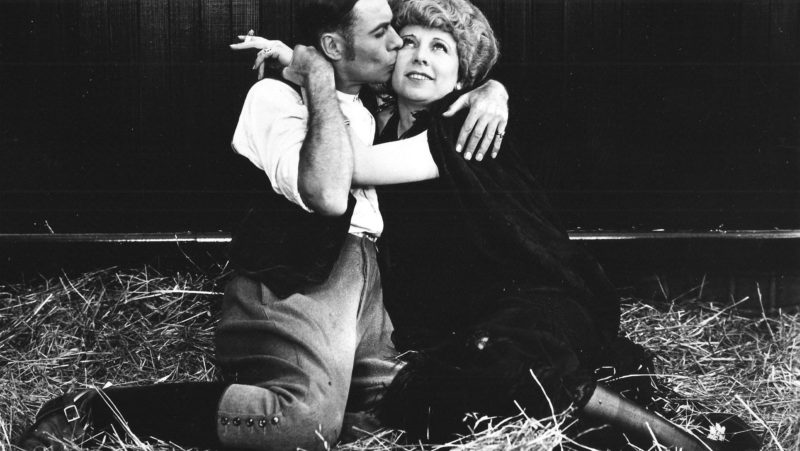

Multiple question marks have been swirling around Merry-Go-Round since it was released in 1923, principally over how much was shot by Erich von Stroheim, and how much was filmed by the director who replaced him, Rupert Julian. On Monday, October 9th at the Teatro Verdi in Pordenone, this legendary, some felt damned, film will be screened in a way that allows us to assess just how much of “the man you love to hate” can still be detected (the answer is, quite a lot). Born in Vienna and moving to the United States when in his early twenties, Stroheim presented himself as the last representative of Central European imperial nobility, also claiming to have served in the cavalry with the rank of officer. In reality he was a Jewish boy from the lower middle class, and his first steps in the world of cinema were as a simple extra, including in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation. With the entry of the United States into the First World War, Stroheim assumed the mantel of the prototypical “bad” German and the domineering, perfidious aristocrat; his life was marked by excess and the desire to impose his idea of cinema with no studio restraints. For this reason he was the bête noire of the Hollywood industry and almost never managed to fully realize his projects. Stroheim’s obsessive attention to detail and complete disregard for budgetary constraints brought him into conflict with the studio brass, and six weeks into the Merry-Go-Round shoot, he was fired by Irving Thalberg, who replaced him with Rupert Julian. The new director, best known for Phantom of the Opera one year later, stuck to the script as faithfully as possible, respectful of Stroheim’s imagining of a decadent world at the end of an era, where a Viennese girl of humble origins falls in love with a nobleman. While we can never know what the film would have been had Stroheim completed it all himself, Merry-Go-Round has now come back to life thanks to an elaborate reconstruction and restoration by Blackhawk Films in collaboration with Lobster Films, Filmarchiv Austria and Det Danske Filminstitut, made with the support of the Sunrise Foundation for Education and the Arts.

Monday is dedicated to larger-than-life characters, including Pierre Loti (1850-1923), a writer, naval officer, traveller, diplomat, sportsman, and member of the Académie française: it’s difficult to imagine how one man could lead so many lives. Loti visited 29 countries, participated in 31 naval military operations and published 61 books, most of which were steeped in exoticism. On the occasion of the centenary of his death, the Giornate pays homage to him with a program (starting today at 5.45 PM) which evokes Loti’s universe through images of the places he loved as well as some fiction shorts inspired by his writings. You will see, among other things, images of the funeral of the great French actress Sarah Bernhardt, a very dear friend of his, who died the same year.

Worth noting is La madre (1917), screening at noon. Directed by Giuseppe Sterni and recently rediscovered and restored by the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, the film gives us the rare opportunity to admire the art of Italia Vitaliani (1866-1938), a relative of Eleonora Duse whose fame, also on the world’s stages, at one time nearly equaled her celebrated cousin. After decades of theatrical activity including as manager, she ventured into film, with La madre being her last important contact with cinema. While she continued to appear on stage and also taught acting, she spent her final years in Milan, alone and largely forgotten. Our screening is preceded by a delightful promotional short film in which we see the director welcoming Vitaliani to her studio and showing her the script.

Preceding La madre is a further installment in our Harry Piel series, Das Teufelsauge (The Devil’s Eye), 1914, screening at 10 AM and starring Ludwig Trautmann. “One wonders whether a real person could truly make such daring leaps and climbs, risking his life at every moment,” wrote the press of the time, and while they were speaking of Trautmann, it was this kind of role that Piel himself became famous for once he also began appearing in front of the cameras, so much so that he was called the Germsn Douglas Fairbanks. Make sure you don’t miss this film’s spectacular dynamiting of a factory.

The Ruritiania series continues later in the afternoon at 4 PM with The Only Thing (1925), directed by Jack Conway. Written by Elinor Glyn (author of last year’s Three Weeks), it’s the story of a beautiful Nordic princess forced to wed a spectacularly ugly Balkan king, but who falls in love instead with a dashing British nobleman. Ample doses of humor plus splendid sets by Cedric Gibbons make this a thoroughly enjoyable piece of escapism, climaxing with an impressive scene of revolutionary terror.

Before then, we’re back to our Origins of Slapstick series at 2.30 PM, with today’s focus on clowns. Following the shorts, the main film is Rêves de Clowns (FR 1924), the only known feature starring the famous trio of French clowns of Italian origin, Les Fratellini, darlings of the public as well as the intellectuals of their day. The most influential clowns of the first half of the 20th century, the Fratellini are largely responsible for the codification of circus clown prototypes, making this rare film, shot in Paris’ Cirque d’Hiver at the height of their fame, an especially valuable record.

The Pordenone Silent Film Festival / Le Giornate del Cinema Muto is made possible thanks to the support of the Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia, the Ministry of Culture — Direzione Generale Cinema, the city of Pordenone, the Pordenone-Udine Chamber of Commerce and the Fondazione Friuli.

Italiano

Italiano

Recent Comments