Il mondo dello spettacolo fu duramente colpito dalla pandemia influenzale del 1918, eppure solo alcune delle vittime più famose, come il regista John Collins, sono oggi ricordate. E che dire degli innumerevoli altri – uomini e donne – che morirono e che sono ora dimenticati, come l’attore Leo Ragusi in Italia, o Donna Drew, la protagonista femminile del film di Ruth Ann Baldwin ’49-’17? Ho scoperto la tragica storia di Ray Bagley, un intraprendente giovanotto del Minnesota che si fece rapidamente un nome come responsabile della promozione di diverse sale, prima di guidare il reparto pubblicità della Triangle e poi diventare redattore e critico della testata di informazione cinematografica Wid’s Daily. Morì di influenza a 27 anni nel novembre del 1918: tutti coloro che lo conoscevano ne furono profondamente addolorati; il delicato compito di avvertire sua madre vedova fu affidato a Lois Weber.

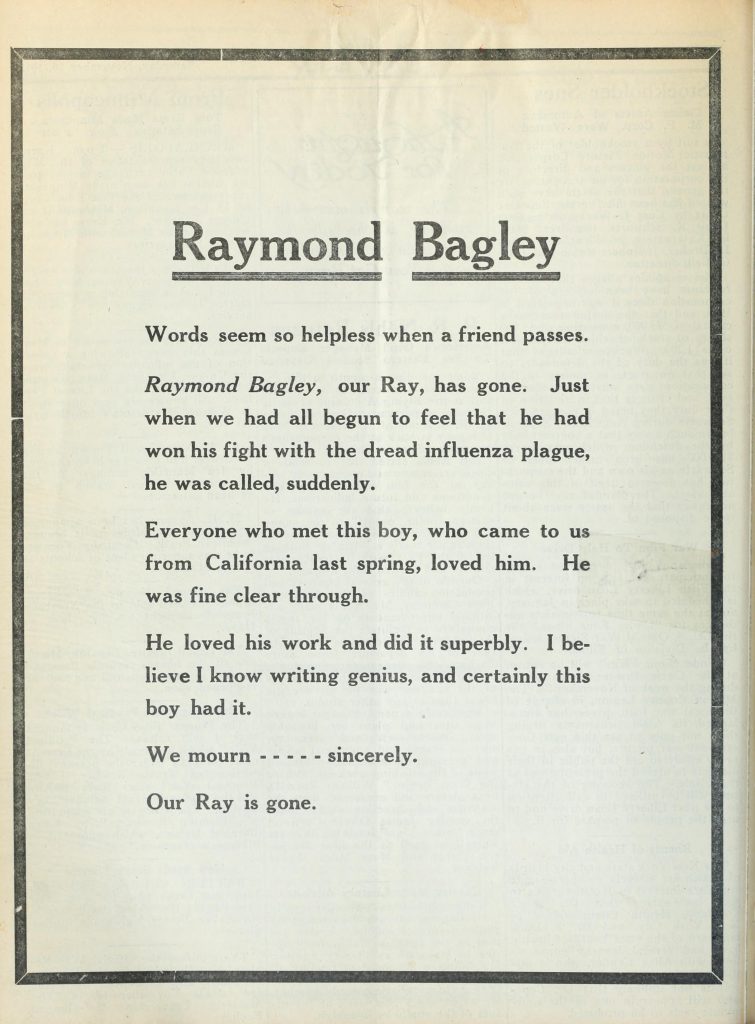

Wid’s Daily, November 16, 1918, back page.

“He was fine clear through.” We don’t use the word “fine” very much in that way anymore, which is a pity since it has something direct and clean about it, something large-scale in only four letters. Each time I say the line in my head, it comes out the same way Katharine Hepburn says “My, she was yar” in The Philadelphia Story, full of wistfulness, promise and a yearning for something lost: Ray was fine. Don’t worry if you’ve never heard of Ray Bagley; I stumbled upon him when looking at some now-forgotten victims of the 1918 flu pandemic, and the notice in Wid’s Daily struck me by its spare emotional candor. If research brings people back to life, I’m especially happy to resurrect Ray, who deserves to be at least a footnote in film history, though frankly returning him to the spotlight fills me with pleasure simply because he was someone good. Someone special.

I’ll get back to Ray in a moment. Flipping through film journals from October and November 1918 is a sobering experience, especially when you scan the obituary notes, shortened to their essence because so many names needed to be crammed onto the pages. The Giornate have done much to return John Collins to his well-deserved place among the leading young directors of the period, and many of us can name several other prominent people in the entertainment field who died during the pandemic. Myrtle Gonzalez, regarded as the first Latina film star in the U.S., died the same day as Julian L’Estrange, an important actor in his own right but now chiefly remembered as the husband of Constance Collier. Three days earlier, thirty-one-year-old star Harold Lockwood succumbed to the virus, a loss movingly noted in La Cinématographie française: “…dont la carrière s’annonçait des plus belle, des plus brillante [sic], et que nous revoyons toujours avec un nouveau plaisir dans les nombreux films qu’il avait tournés avant d’être emporté en quelques jours par cette grippe mondiale”.[1]

What of those so quickly forgotten? What of Italian actor Leo Ragusi, who began working for Ambrosio in 1909 and soon developed into the kind of on-screen personality consistently welcomed by the critics? In 1913 he moved to Pasquali, followed by Jupiter, Aquila and Milano Film before serving in the War first in the artillery and then in a management role at an airplane factory. He died of the flu, his memory, like so many, rapidly sinking with barely a trace.[2]

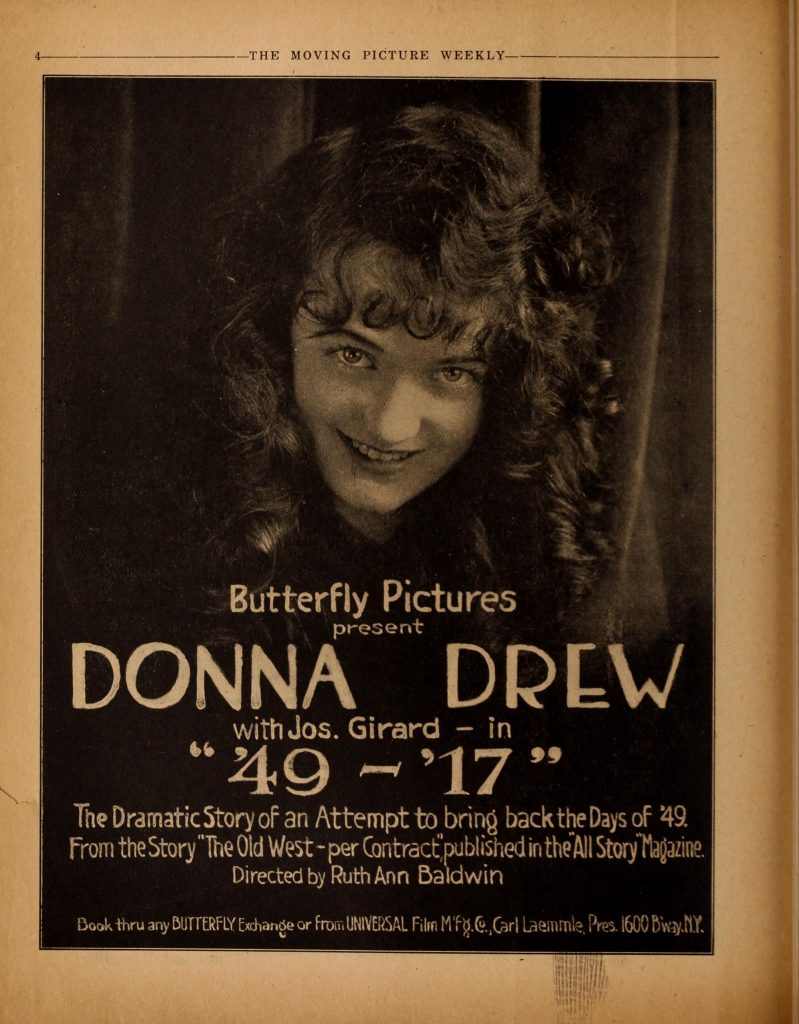

The Moving Picture Weekly, September 29, 1917, p. 4.

Or Donna Drew, female lead of Ruth Ann Baldwin’s ’49-’17, whose place in public memory was already whittled away to simply “Mrs. Arthur Moon” when she died a mere nine months after her last released feature, the cross-dressing (male-to-female courtesy of Jack Mulhall) espionage drama Madame Spy? Born Donna Anderson in 1897, she was 18 when she married vaudeville performer and fellow Salt Lake City resident Arthur Morse Moon, who was making a name for himself in Margaret Whitney’s musical comedy The Wrong Bird (with future star Betty Compson in the chorus and playing the violin). One year later she appeared in a locally produced three-reeler called A Twentieth Century Courtship (1916) before joining her husband in California and signing a contract in 1917 with Universal to appear under their Butterfly banner. As usual, the studio invented a backstory, claiming she was a member of the Willard Mack-Marjorie Rambeau stock company (which was true of Arthur, not Donna), and telling the press she was born Donna Moon but changed it to Donna Drew because it better suited her personality.[3]

At the start the publicity machine seemed to do a good job promoting their new actress, yet after Madame Spy it’s hard to know exactly what happened. In ’49-’17, her only known surviving feature, she has an appealing quality reminiscent of Dorothy Gish, but either Universal felt she wasn’t distinctive enough, or for unknown reasons she chose to step away from the cameras – she completed her last screen role in September 1917, a five-reeler called The Ghost Girl directed by Jack Wells, which however wasn’t released until after her death in January 1919 when it had been cut down to two reels.[4] Whatever the reason for stopping film work, she shifted to vaudeville and joined Arthur, who’d been working steadily for the Vogue Motion Picture Company, Keystone and Triangle, on the Pantages circuit with a revival of The Wrong Bird beginning in June 1918.[5]

That September they’d been playing in central Canada, moving down to Montana the following month just when the flu pandemic was gaining strength. Myrna Loy recalled what it was like in her home city of Helena: “It devastated the town. You couldn’t get nurses. You couldn’t get doctors; I mean, you got them to stop in and then they would disappear into the night. People walked the streets with makeshift surgical masks over their mouths.”[6] Loy, her mother and brother all became sick and recovered; her father wasn’t so lucky, dying in the weeks after nursing his family back to health. It was here in Helena that Arthur Moon and Donna Drew both became ill while staying at the Placer Hotel (located, I need to add, on Last Chance Gulch) – Arthur was one of the first flu deaths in the city, succumbing on October 17th, at the age of 30 or 31.[7]

Donna, too sick to leave town, was joined by her parents and brother while Arthur’s body was taken to Salt Lake City for the funeral. She seemed to rally, but then just one day after Arthur’s burial she too expired, aged 21. Her death was covered by the newspapers and trade publications, though in many cases she was described as little more than an adjunct to her husband: “Mrs. Arthur Moon Dies of Influenza” was the headline in The Helena Daily Independent. For her family, the losses didn’t end there: Donna’s father Walter Anderson caught the virus when he was looking after her in Helena. He made it back to Salt Lake City but, too ill to attend her funeral, was dead two days later.[8]

THE CLEVEREST KID IN THE GAME

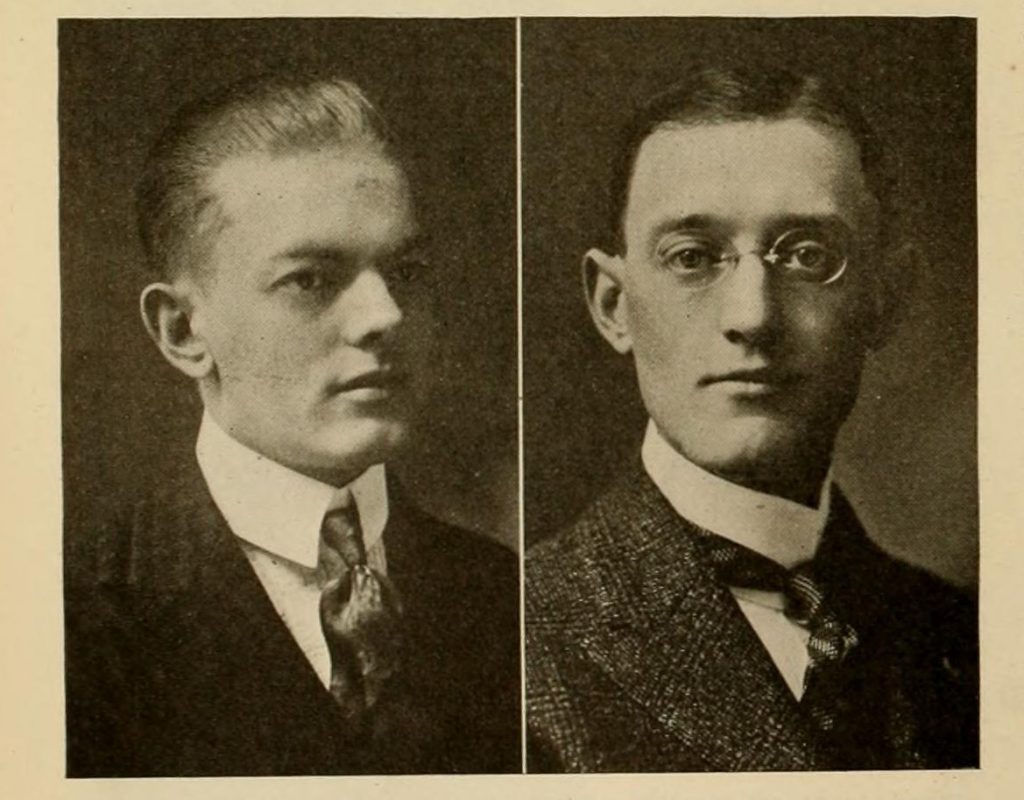

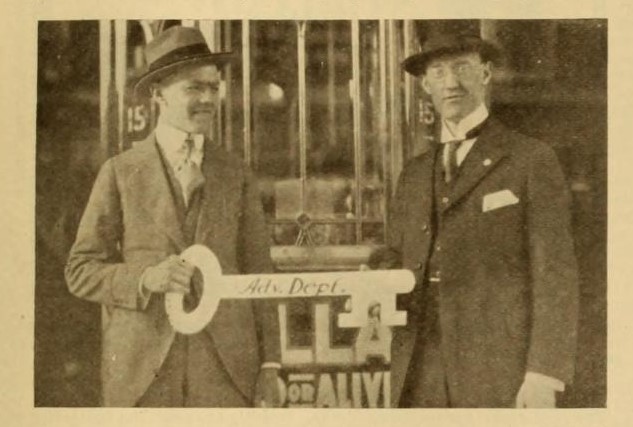

Ray Bagley and Ralph R. Ruffner, The Moving Picture World, February 12, 1916, p. 942.

Detroit, Minnesota was a small community of about 1,500 when Raymond Bagley was born in 1891, before the town was rechristened Detroit Lakes and became a seasonal vacation destination. Lying 72 kilometres east of Fargo, North Dakota, it had a significant population of first- and second-generation immigrants from northern Europe, like Ray’s mother Lena, whose Norwegian background can be traced in her son’s boyish Nordic features. Ray wasn’t quite ten when his father Frank, a saloon keeper, died; Lena appears to have remained in town, eventually working as a housekeeper in the Hotel Minnesota, but by 1910 Ray had travelled west to Missoula, Montana, near the Idaho border, where he got a job as a window dresser and advertising manager for a clothing store. What struck me while looking into his life is how personal newspaper reports got about Ray from early on, how he clearly charmed everyone he met. In Missoula he became known for entertaining at fraternal functions with quick cartoon sketches, one of which made its way into the local newspaper in 1914; its inside jokes about poultry fairs fall flat now, and the drawing is derivative, but he clearly became a favourite of the local community almost immediately, and the energy he displayed as a “a lightning crayon artist” was a characteristic remarked upon by all who mentioned him.[9]

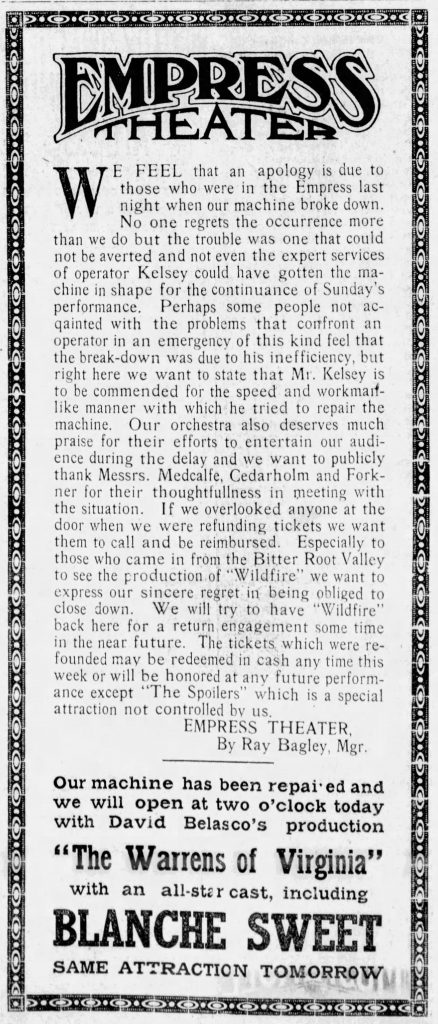

He moved into the entertainment business in the summer of 1914, succeeding the future Academy Award winning animator Fred Quimby as manager of the Empress Theater, opened one year earlier. “Mr. Bagley is popular in Missoula and the best wishes of his friends go out to him in his new venture,” wrote the local paper. What comes through powerfully in the otherwise impersonal reportage of most newspapers is Ray’s dynamism: he was a go-getter, the kind of guy who’d enter contests in the papers and win them, too. “Mr. Bagley took charge as manager of the Empress theater a few months ago and has rapidly developed into one of the live wires in the business.” He was an innovator in Missoula who understood that the way to develop a loyal audience is to treat them with the warmth and respect of friends, as can be seen in the advertisement he took out in March 1915 apologizing for a mishap during the projection of the Lillian Russell film Wildfire.[10]

Empress Theater, Missoula, Montana, April 1913. Courtesy: Historical Museum at Fort Missoula

The Missoulian, March 8, 1915, p. 2.

He knew his game, and he knew how to work it well enough to capture the attention of the national trade publications, where he’s first mentioned in April 1915 thanks to a crafty little stunt where he nicely played off World Pictures and Paramount. The Empress was screening films from Fox, World, and Paramount each week, so like the shrewd marketing man he was, Ray wrote to at least the latter two, saying what a pleasure it was to work with them: “You’ve got a great organization” he told Lewis Selznick at World, after alerting the studio to his innovative “Midnight Matinee” screening of Old Dutch. Naturally Selznick jumped at the chance of tooting his own horn and took out a full-page advertisement in Motion Picture News hyping Bagley and his clever marketing of World’s releases. What he didn’t know is that Ray had also written to Jane Stannard Johnson at Paramount, laying on the compliments with an even thicker brush: “You are making EXHIBITORS out of men who have started a FLICKER SHOP. If an exhibitor can’t make good with Paramount Pictures and the power behind them, he is letting the office boy open his mail.” Not to be outdone by Selznick’s self-promotion, Stannard Johnson took out a full-page ad one week later with a headline shouting “Misstatement,” taking her rival to task for pushing his special relationship with Ray when the truth was that the Empress screened World films but once a week, whereas Paramount features were on the programme four times a week. Ray couldn’t have paid for better self-publicity.[11]

Eight months after drawing national attention to the Empress’ marketing campaigns, Ray was recruited by exhibitor Ralph R. Ruffner to become advertising manager at the 1,000-seat Liberty theatre in Spokane, Washington. “His friends regret to see Mr. Bagley leave Missoula, but they feel confident that he will make good in his chosen profession,” wrote the local paper as he set out further west. It was while in Spokane that Ray was first mentioned by the grandiosely-named Epes Winthrop Sargent in his influential “Advertising for Exhibitors” column of The Moving Picture World. Sargent was the doyen of film publicity mavens, author of Picture Theatre Advertising (1915) and a tireless stumper for sharing new ways of film promotion by soliciting ideas and encouraging his readers to write in with their ad campaigns (he was also a critic and screenwriter deserving of a biography of his own). Through the pages of the magazine, Sargent became Ray’s mentor and promotor, touting his creative salesmanship fourteen times in his column and often reproducing parts of Ray’s letters, even publicly scolding the eager Minnesotan when he didn’t hear from him for a while.[12]

Ray Bagley and Ralph R. Ruffner, The Moving Picture World, June 10, 1916, p. 1875.

Not quite a year after arriving in Spokane, Ray’s former boss in Missoula, Otis Hoyt, hired him as publicity manager for the new 900-seat theatre he was having constructed in Long Beach, California, also called the Liberty (future star Cullen Landis was an usher). Sargent published a cute photo in his column of Ray before departure, handing an oversized key for the advertising department to Ruffner, who calls his now ex-employee “The cleverest kid in the game.” The photo is blurry but Ray’s waggish grin, turned towards Ruffner’s more posed smile, significantly contributes to my sense of him as a delightfully impish young man with a bright future and plenty of gumption. Several months later, Sargent admiringly called him “one of the natural born hustlers,” a designation usually guaranteed to raise my hackles, but in light of all the affectionate language used about him by colleagues, it’s impossible not to be charmed. Ray’s mother Lena joined him in California, where he rented a bungalow for the two of them just a couple of blocks from the beach – it was a long way from the inland plains of eastern Minnesota, and I imagine it was the first time either of them ever saw the ocean, which they could probably now hear from their home on quiet nights.[13]

KEYSTONE-TRIANGLE AND AN INSURED ADAM’S APPLE

Clearly not one to let opportunity pass, Ray moved jobs once again a year after arriving in Long Beach, taking charge of the publicity department at Keystone-Triangle in April 1917: “while Manager Hoyt regrets exceedingly to lose Bagley, nevertheless he, as well as his many other friends in Long Beach, rejoice over the young man’s good fortune.” Given that one of their stunts was to put the Triangle logo, in the correct colours, on candy handed out in the cinema, it shouldn’t be surprising that the studio realized this was a man for them.[14] I’ve not studied how Triangle advertising evolved in this period, so I can’t weigh in on what changes Ray instituted, but I did uncover one publicity stunt which deserves at least a minor place in film history lore. If you do a short internet search on insurance policies for actors’ body parts, you usually get sites saying that Ben Turpin’s was the first of the gimmick policies – his crossed eyes are said to have been insured by Lloyds of London in 1921, in case they should ever straighten themselves out. As usual, this kind of murky received wisdom is itself the product of a publicity man’s regurgitation of another publicity man’s stunt. Whether Turpin actually had a policy out is open to question, but he certainly wasn’t the first performer to have a body part insured. That honour appears to belong to the violinist Jan Kubelik, whose fingers were reported to be insured by Lloyds in 1901 for $100,000 – unsurprisingly the policy, if it ever existed, was taken out by showman extraordinaire Daniel Frohman. Once the news got out, Frohman’s gimmick was embraced by other publicity gurus eager to get their clients in the papers: Adelina Patti was said to have her vocal chords insured for £1,000 per performance, while Lina Cavalieri had a $50,000 policy just in case she came down with a sore throat. It was reported that each of La Belle Otero’s toes was protected by a $16,000 policy, Paderewski’s hands were insured for £10,000, and Ruth St. Denis’ arms were indemnified for $50,000, all before 1910 (the amounts vary according to the source).[15]

Ziegfeld Follies showgirl and professional dancer Vera Maxwell supposedly had her feet insured in 1913 for $100,000 – or was it francs? – with a special clause added in case a pedicure went awry (there’ll be more on Ms. Maxwell in my next post). Better known are the flurry of articles that came out in 1915 when it was reported that each of Chaplin’s feet were insured for $50,000, rising to $150,000 should they both be injured. David Robinson believes this to be an invention of Essanay’s publicity department, which makes complete sense – after all, as Harry Reichenbach, the man who claimed to have invented film publicity, wrote, “I could fool a hundred editors into accepting bits of fancy as front-page news and get a hundred thousand columns in headlines and news stories for things that had never happened.” Why all this background? Because in September 1917, Ray claimed to have engineered a policy to insure against any damages to Keystone comedian George H. Binn’s Adam’s Apple, apparently used by Binns to make his bowtie perform to comic affect. Not just the Adam’s Apple, covered up to $10,000, but each eyebrow had a $5,000 policy. Naturally the newspapers covered the announcement, but the story and the comedian were both soon forgotten (British-born Binns [1886-1918] moved to L-KO before becoming a victim of the flu pandemic himself).[16]

I’ve gone into all this because I believe there’s a case to be made for Ray being the originator of the truly superfluous gimmick insurance policy. A dancer’s feet have value, a violinist needs his or her fingers, the loss of a singer’s voice means the end of a career. But an Adam’s Apple? Could Ray have initiated the trend supposedly begun with Ben Turpin’s eyes and continued as late as 2007 when America Ferrara’s smile was reportedly insured for $10 million?

LOIS WEBER BREAKS THE NEWS

Five jobs in four years doesn’t sound like a good way to pursue a career, but this was the entertainment business, where things moved quickly and opportunities for a bright go-getter like Ray were there for the taking. One year after joining Triangle, in the spring of 1918, he packed up his things again and moved across the country from Culver City to New York for an exciting new job as Wid Gunning’s assistant on the trade paper Wid’s Daily.[17] It was a further reinvention in which he took on the roles of editor and critic, and once again Ray won over his colleagues to such a degree that after a few months, Gunning was planning on putting him in charge of the New York bureau. That’s when tragedy struck. Sometime in early November, Ray contracted the flu, resulting in a chain reaction of grave infections: pneumonia, pleurisy and then a heart attack. Like Donna Drew one month earlier, it appeared he was recovering, but his body gave out and he died at the age of 27. “Our Ray is gone.”

We know a surprising amount about his end thanks to a detailed obituary in the Long Beach Daily Telegram[18] which reproduces the telegram (incorrectly dated) that a clearly distressed Gunning sent to Otis Hoyt at the Liberty theatre, included here:

I assume Gunning was a good friend of both Lois Weber and Ernest Shipman (husband of Nell, herself brought perilously low by the flu), which is why he telegrammed asking that they break the news personally to Lena Bagley. I also imagine Gunning knew that Weber was the kind of sensitive person who’d be as gentle and supportive as possible in such an agonizing moment. Ray was all Lena had: her sister died in 1913, and he received a draft deferral because he was his mother’s sole support. Gunning handled all the funeral expenses, which may have included Lena’s unimaginably sad train journey from her home in Los Angeles to Detroit, Minnesota, where she buried her son in a grave next to her husband’s. Alone with nothing to keep her in California (I presume she would eventually have gone to New York with Ray had he lived), she moved back to Minnesota by 1920, living as a boarder and working as a seamstress; ten years later she was living with a cousin. Lena died in 1939, at 71.[19]

I can’t quite explain why Ray’s story touches me so deeply. His youth, no doubt, and the way he won friends so easily. The headline of the Long Beach Daily Telegram obituary ran “Popular Publicity Man Dies in New York City,” itself a testimony to the affection felt by the men and women he met. Forty-nine years after his death, a gentleman in Missoula wrote to the local paper recalling that Ray aspired to being the best-dressed man in town[20] (another reason for me to like him), but I wonder whether anyone has mentioned him since. It’s time for him to be remembered. Ray was fine clear through.

Jay

Big thanks for help with this post go to Ted Hughes and the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula; Brian N. Chavez and the Historical Society of Long Beach; and David Robinson.

[1] “whose career promised to be one of the best and brightest, and who we always see with new-found pleasure in the many films he made before being carried off in a matter of days by this pandemic”: Arlecchino, “Fantômes Aimés?,” La Cinématographie Française, March 6, 1920, p. 36. For a personal tribute to Lockwood, see Adèle Howells, “Harold Lockwood,” La Cinématographie Française, June 7, 1919, p. 9.

[2] “La morte dell’attore Leo Ragusi,” La vita cinematografica, October 7-15, 1918, p. 92.

[3] “Society,” The Herald-Republican [Salt Lake City], April 15, 1915, p. 5; “Thanksgiving Show Treat,” The Logan Republican, November 24, 1914, p. 7; “Pretty Salt Lake Girl Who Stars in Three Reel Film Produced in This City,” The Salt Lake Telegram, August 13, 1916, p. 9; Steve Massa, Slapstick Divas: The Women of Silent Comedy (Albany, GA: BearManor Media, 2017), p. 149; G.P. Harleman, “News of Los Angeles and Vicinity,” The Moving Picture World, May 19, 1917, p. 1134; “Donna Drew Chooses Her New Name,” The Moving Picture Weekly, August 11, 1917, p. 9. She also graces the cover of that issue.

[4] The Moving Picture World, September 15, 1917, p. 1681; The Moving Picture Weekly, January 11, 1919, p. 31.

[5] “Arthur Morse Moon Coming to Pantages in Local Play,” The Herald-Republican-Telegram, June 9, 1918, p. 11.

[6] James Kotsilibas-Davis and Myrna Loy, Myrna Loy. Being and Becoming (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), p. 21.

[7] “Another Death in Helena,” Great Falls Daily Tribune, October 19, 1918, p. 4; “Arthur Morse Moon Dies of Influenza,” Deseret Evening News, October 18, 1918, p. 2.

[8] “Mrs. Arthur Moon Dies of Influenza,” The Helena Daily Independent, October 25, 1918, p. 5; A.H. Giebler, “News of Los Angeles and Vicinity, The Moving Picture World, November 16, 1918, p. 727; “W.S. Anderson Dies,” The Helena Daily Independent, November 1, 1918, p. 5.

[9] Information on Bagley’s family comes from the 1900 census: U.S. Census Bureau (1900), Detroit, Minnesota; “How to Get Rich on Apples and a Side Line of Poultry,” The Missoulian, February 1, 1914, p. 4; “’Best People on Earth’ Give Greatest Show in the World Tonight,” The Missoulian, April 28, 1913, p. 2.

[10] “Ray Bagley is Now Manager of Empress,” The Missoulian, August 11, 1914, p. 10; “By Observant Eyes Ray Bagley Enriched,” The Missoulian, December 11, 1914, p. 7; The Missoulian, March 8, 1915, p. 2.

[11] Motion Picture News, April 10, 1915, p. 4; “Live Wire Exhibitors. Midnight Matinee is a Success,” Motion Picture News, April 10, 1915, p. 41; Motion Picture News, April 17, 1915, p. 19.

[12] “Bagley Advances in His Chosen Profession,” The Daily Missoulian, May 17, 1915, p. 8; Epes Winthrop Sargent, “Advertising for Exhibitors,” The Moving Picture World, July 24, 1915, p. 641; Sargent, “Advertising for Exhibitors,” The Moving Picture World, December 16, 1916, p. 1636.

[13] “Opening of New Theater Tonight Realizes Dreams,” The Long Beach Press, June 15, 1916, p. 10; Sargent, “Advertising for Exhibitors,” The Moving Picture World, June 10, 1916, p. 1875; Sargent, “Advertising for Exhibitors,” The Moving Picture World, December 16, 1916, p. 1637; “Personal Mention,” The Long Beach Press, April 25, 1916, p. 4.

[14] “Ray Bagley Leaves Liberty to Accept Triangle Position,” The Long Beach Press, April 30, 1917, p. 2; Sargent, “Advertising for Exhibitors,” The Moving Picture World, February 12, 1916, p. 942.

[15] “Behind the Scenes. Taking Risks in Hollywood!,” Hollywood, February 1937, p. 45; “Kubelik’s Arm Insured,” The Sun [Baltimore], December 21, 1901; “Eyes Worth $50,000 and Hands $5,000 Per Day,” Saint Mary’s Beacon [Leonard Town, MD], June 12, 1902, p. 4; “$16,000 For a Sore Toe!”, The San Francisco Examiner, December 2, 1906, p. 64; “Her Arms Valuable,” The Salt Lake Tribune, February 6, 1910, p. 11.

[16] “Two Feet Valued at $100,000 Insured By Chicago Firm,” The Inter Ocean [Chicago], December 30, 1913, p. 7; “Des Pieds de 100,000 francs,” Le Journal, January 17, 1914, p. 6; “Charles Chaplin Insures His Feet for $150,000,” Motion Picture News, April 24, 1915, p. 50; Harry Reichenbach, in collaboration with David Freedman, Phantom Fame, or, The Anatomy of Ballyhoo (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1931), p. 8; Charles Fuir, “Hollywood Hookum,” Motion Picture News, September 1, 1917, p. 1487; “Deaths,” Variety, November 15, 1918, p. 45.

[17] Guy Price, “Coast Picture News,” Variety, May 3, 1918, p. 41.

[18] “Death Came Suddenly,” Wid’s Daily, November 16, 1918, p. 2; “Popular Publicity Man Dies in New York City,” Long Beach Daily Telegram, November 15, 1918, p. 12.

[19] Draft registration card for Ray Bagley, June 5, 1917; U.S. Census Bureau (1920), Detroit, Minnesota; U.S. Census Bureau (1930), Edina Village, Minnesota; Lena Hanson Bagley, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/70786766/lena-bagley.

[20] “Odds and Ends,” The Missoulian, December 22, 1967, page 1.

English

English

Commenti recenti