Nel mio ultimo post, ho iniziato la storia di Gertrude Wilkins (alias, Josephine Howard) e degli uomini della sua vita. In questa seconda parte lei fa solo delle brevi apparizioni perché mi concentro maggiormente sul suo primo marito, il ballerino Jack Jarrott, con una significativa digressione sulla vita della sua compagna di ballo, Joan Sawyer. Benché il nome della Sawyer si possa trovare in libri e articoli sulla mania della danza degli anni ’10 e la sua sia un’importante presenza negli studi su Rodolfo Valentino, ho scovato un sacco di notizie in più che riguardano i suoi primi anni e dalle quali emerge il suo atteggiamento squisitamente trasgressivo rispetto alle abitudini sessuali dell’epoca così come la sua risoluta determinazione a farsi strada con ogni mezzo necessario. Nel terzo capitolo, completerò la tragica vita di Jarrott, per continuare con i due successivi mariti della Wilkins, soffermandomi anche sul curioso ritorno di lei agli onori delle cronache sei anni dopo la sua morte.

The timeline for Gertrude Wilkins – Josephine Howard’s real name – is riddled with frustrating lacunae. She returned from Europe to New York with her new husband Jack Jarrott in the autumn of 1913, but then sometime in early 1914 was back in England, why and exactly when is unclear. Maybe it was to tie up loose ends, maybe she had some commitments, but when she returned to New York on the RMS Olympic in March, she was using the name Josephine Gertrude Howard and put London as her permanent residence; tellingly, she gave her mother’s address in Jersey City as her destination, rather than an apartment in New York she might have been sharing with her husband.[1] Jack meanwhile had just been hired by leading exhibition ballroom dancer Joan Sawyer to partner her at the Persian Garden, the chic establishment set up on the third floor of the Palais de Danse (part of the Winter Garden theatre) at Broadway and 50th Street. Conceived as a rival to Irene and Vernon Castle’s new dancing palaces Castle House and the Sans Souci, both launched in December 1913, the Persian Garden became an instant success, with Sawyer and Jarrott’s photographs popping up in newspapers and magazines throughout the country.

BESSIE JOSEPHINE MORRISON BECOMES JOAN SAWYER

Of all the people in Jarrott’s life, Sawyer (1880-1966) is the one whose name turns up most frequently, largely because she hired Rudolph Valentino (billed as “Signor Rudolph”) in 1916 as one of her many dance partners. Histories of their professional collaboration invariably devote most space recounting how he named her as co-respondent in the divorce proceedings between Bianca Errázuriz and John de Saulles, yet this was hardly Sawyer’s first – or last – time being named in relationship lawsuits. I’ve uncovered new information that brings into even sharper relief Sawyer’s deliciously transgressive attitudes towards the sexual mores of the day, which is why I’m making a detour here to fill in her story. While her important role in the dance craze of the early to mid-teens is well-known, no one seems to have processed how her strong-minded, sexually unconventional conduct whittles away the unsustainable dividing line between pre- and post-World War I female behavior.

Howard Rye and Tim Brooks, first in their Storyville series and then in Brooks’ fundamental 2004 volume Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919 are the only scholars to delve into Sawyer’s early years, yet the information is incomplete.[2] Born Bessie Josephine Morrison in Cincinnati in 1880, she was sent as a child to El Paso to live with another family but at some point returned to Ohio; details are murky though it’s safe to say her childhood was unstable. The trail of documents begins in October 1902 with her marriage to Alvah Hayden Sawyer, a travelling salesman.[3] The relationship, rocky from the start, rapidly disintegrated once they moved to the Inside Inn, an enormous hotel on the grounds of the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition (the World’s Fair of Meet Me in St. Louis). Alvah got a job as the hotel’s private detective, which is ironic given that his wife began staying out very late with officers from the Philippine Constabulary based in the city, as well as an unnamed West Point cadet. Bessie didn’t hide her infidelity very well – Alvah intercepted a note and even punched one of the Filipino officers in the face – but maybe it didn’t really matter since clearly she was through with this marriage, even if she did keep his surname for the rest of her life. In reporting Alvah’s filing for divorce, some newspapers played up the interracial angle as a way of further condemning his wife’s behaviour; they also reported that in July 1904, against her husband’s wishes, she joined the chorus of Bolossy Kiralfy’s World’s Fair musical pageant, the Louisiana Purchase Spectacle – her first theatrical appearance. By the time the divorce was finalized in December 1905, Bessie had assumed the name Joan Sawyer and was in Chicago, “studying for the stage.”[4]

While it’s hard to ascribe character traits when lengthy personal accounts are lacking, I think I’m safe in saying she wasn’t anyone’s best friend. In August 1906 she testified against her fellow chorine Lola Montez Walker (yes, the Walkers of Beardstown, Illinois really named their daughter Lola Montez) in her breach of promise suit, and while Walker would deny on the stand knowing Sawyer, that seems unlikely given they were both in Kiralfy’s show as well as George Sidney’s Busy Izzy (aka Bizzy Izzy) touring company.[5] Perhaps Walker’s suit that summer inspired Joan two years later to file her own claim for a whopping $100,000 against millionaire playboy Byron D. Chandler, who she asserted had promised to marry her before she knew he already had a wife. Sawyer’s desire for compensation proved stronger than any concern about her reputation: she testified that they’d lived as husband and wife in Boston and she had several accounts in major department stores under his name. Three months after bringing the case to court, and without the knowledge of her lawyer, Joan dropped the charges; decades later it was alleged she’d privately wrangled a settlement out of Chandler for $23,765 (equivalent to nearly $706,000 today), an odd sum so precise I’m inclined to think the figure could be genuine.[6]

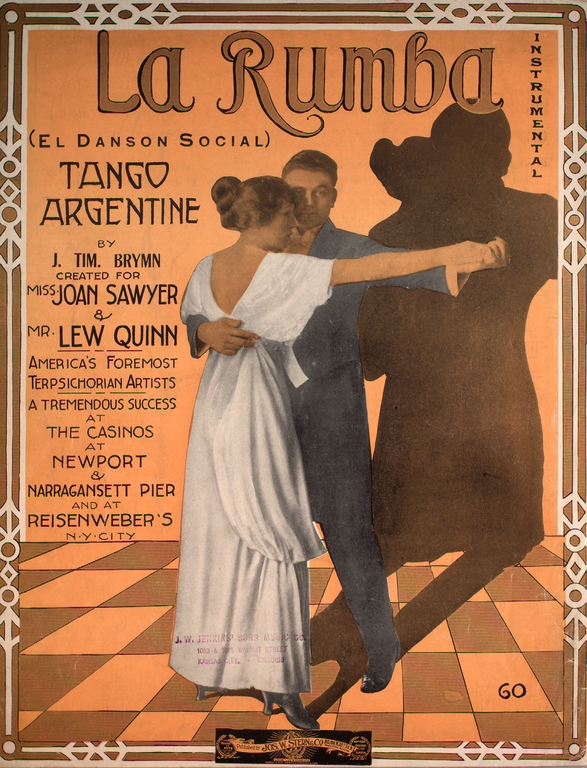

Sawyer wasn’t famous enough for the negative publicity to hurt her career, which in truth hadn’t taken her much further than some touring companies and a small role in the 1908 Broadway production of The Merry-Go-Round. Apart from a nationwide advertising campaign promoting Parisian Sage Hair Tonic, it’s unclear what she was doing between 1909 and early 1912 – perhaps living off her Chandler settlement. She must also have been perfecting her dance moves, because in February 1912 she stepped in to partner Maurice Mouvet, the most famous exhibition dancer of the period, when his associate Madeleine d’Harville suddenly ran off with Miles Mander’s younger brother Alan. Though their collaboration at Louis Martin’s restaurant was very brief, Mouvet’s cachet offered the break she needed, and later that year she and Lew Quinn were dancing for society’s grandest names in the fashionable summer resort of Narragansett.[7]

Following that gig, Sawyer became the dance instructor for New York’s elite, first at Reisenweber’s and then at the newly instituted Jardin de Danse on the roof of the New York Theatre, earning her the nickname “the dancing pet of the 400.”[8] That fall of 1913 was particularly busy: in addition to daytime dance classes for the ladies who lunch and nightly shows for New York’s sophisticates, she and Wallace McCutcheon made a three-reel dance instruction film for Kalem, Motion Picture Dancing Lessons, released October 29th, in which they taught viewers how to do the tango, the Turkey Trot, and the Hesitation Waltz. By all accounts it was an innovative film that showed McCutcheon and Sawyer practicing their steps in a studio, with cutaways to just their legs and feet, followed by scenes in a New York cabaret of the instructors and the public performing the dances (the Kalem Kalendar and Moving Picture World give conflicting reports on the order of scenes).[9] Sadly, the film is believed lost.

JEANNETTE LEONARD GILDER

Arthur Williams, “Two Feminists, And Dance Managers,” Vanity Fair, August 1914, p. 45

I’m very much aware of the pitfalls inherent in hypothesizing about sexual behaviour when direct evidence is lacking – if you’re not in their bedroom yourself, how can you know? – but I’m equally tired of commentators denying sexual activity simply because there’s no concrete proof. So I’m going to go out on a reasonably sturdy limb here and state that Sawyer was bisexual. I say this not just because the clearly besotted literary critic Jeannette L. Gilder suddenly became her manager in January 1914 and set her up in the Persian Garden, but this combined with a 1929 lawsuit in which Sawyer was sued for the alienation of a businessman’s wife’s affections make the signs too obvious to ignore. Gilder (1849-1916) was a fascinating figure, an important voice in the intellectual life of the U.S., and today almost completely forgotten apart from her anti-suffragist stance. Yet she was a literary magazine editor, critic, well-respected author (including The Autobiography of a Tom-boy) and friend to Mark Twain and Walt Whitman. Her carefully cultivated mannish exterior positively screams “queer icon,” so why has she been largely ignored?

Far more attention has been paid to her friend the literary and theatrical agent Elisabeth Marbury, perhaps because her relationship with Elsie de Wolfe has been extensively discussed in subsequent decades and embraced in LGBTQ histories. I’ve not seen it conjectured, but I do wonder whether Marbury and Gilder were lovers at one time – although the former was in a relationship with de Wolfe by the late 1880s, her friendship with Gilder appears to have been intimate (I’m consciously shielding myself within that word’s ambiguity). This hardly constitutes proof, but it’s impossible not to read between the lines of this 1902 article: “Miss Gilder, whose appearance is most peculiar, as she is very masculine and dresses to accentuate it, is a bosom friend of Miss Marbury, and they take their yearly vacation together.”[10] I find it odd that Marbury doesn’t mention her “bosom friend” in her 1923 autobiography, My Crystal Ball: Reminiscences, which leads me to wonder whether they might have had a falling out, perhaps around the time that Gilder took on the role of theatrical agent to Joan Sawyer, in direct competition with Marbury’s professional sponsorship of Irene and Vernon Castle. I hasten to add this is pure speculation.

Gilder saw Sawyer dancing at the Jardin de Danse sometime in late 1913 and was smitten: “The moment I observed her beauty and wonderful charm as exemplified in her dancing I was thrilled and amazed. I made her acquaintance that evening and told her that I thought her dancing was a revelation. This little talk led to many visits.”[11] Can’t you picture it? A suited Gilder seated at her table in rapt attention, jauntily shooting her cuffs and beckoning Sawyer over, working all her charms on the outwardly graceful but inwardly calculating dancer thirty years her junior. By Gilder’s telling, she went to Lee Shubert, reminding him that she was the one who introduced him to Nazimova, Julia Marlowe and E.H. Sothern, all major stars; now he could have a new one in this rising terpsichorean (in Gavin Lambert’s Nazimova biography, he claims it was Gilder’s brother Richard Watson Gilder who introduced the Shuberts to Nazimova[12]; I hope to sort this out once the Shubert Archives re-open). The result was that Shubert leased the third-floor cabaret space in the Winter Garden to Sawyer, and Gilder took over management of her career from William Morris. In October 1913, Sawyer and McCutcheon were earning $450 a week; in December she was reportedly offered $1,200[13] – a testimony not only to her fast-rising popularity, but to the dance craze in general, ruled by the Castles but with Sawyer close at their heels. Marbury had installed her charges at Castle House and Sans Souci, so now it was time for Gilder to gild her protégée in the Persian Garden, with Jack Jarrott as her partner.

SAWYER AND JARROTT

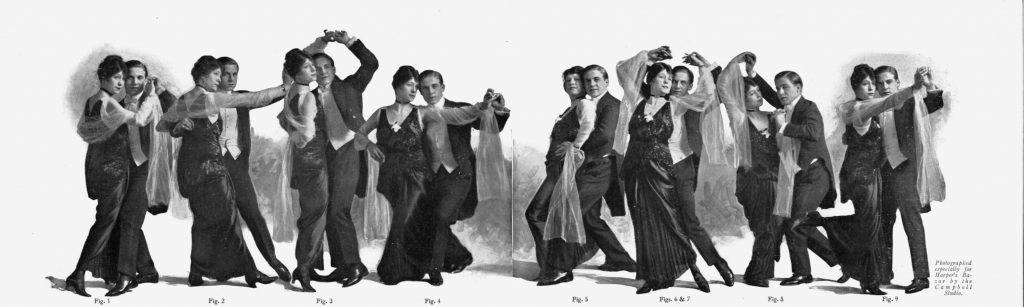

Joan Sawyer, “The Maxixe. A Slide, a Swing and a Throw away,” Harper’s Bazar, December 1914, pp. 14-15

Sawyer was 34 when she really made it big, rather old for a dancer even if she admitted to being younger by nine, sometimes ten years. Jarrott was around 27 and from what we can glean from newspapers he was quite a different kind of dancer, immersed in ragtime and buck-and-wing rather than Sawyer’s preferred waltz and minuet. She’d capitalized on being society’s pet by maintaining an aristocratic, “exquisitely refined” manner in public, never allowing “the least suggestion of the sensual to enter into any of her dances,” but that could get old pretty quickly, and not everyone appreciated the studied elegance: “Miss Sawyer still holds the medal for iciness and frigidity, and when she happens to permit a smile to illumine her classic features, the whole house gasps. Possibly it’s an accident, but more accidents of a like nature would improve the turn.”[14] Fortunately, Joan was adaptable in public as well as private life, and Jack gave her exactly what she needed: energy, and probably a bit of sass. They still performed the expected society dances, but they mixed it up with more original numbers, like Jack’s “Congo Tango,” and the innovation shot them to the top; just a few weeks into their partnership, they were offered $1,000 a week at the Palace, the mecca of vaudeville theatres.

Several critics noted that Joan had finally loosened up with Jack: “Miss Sawyer is…dancing better with Mr. Jarrott than any other of her several floor partners in the past. Always rather a marbleized dancer, Miss Sawyer now displays evidence of amiability, often smiling while stepping with Mr. Jarrott, who is a trotter by nature and profession, not having been plunged into it through accidental discovery.”[15] I like to think there were two reasons why Joan was becoming a better, less rigid dancer: one was Jack, and the other was the African-American band that played for them. The Persian Garden wasn’t the first place where Sawyer worked with black musicians: we know she and Lew Quinn were backed by black musicians in the summer of 1913 at Narragansett (quite possibly J. Tim Brymn and members of James Reese Europe’s Clef Club orchestra, who were performing in nearby Newport), and it’s likely she appeared with James Escort Lightfoot’s Gardenia Quintette when dancing at Reisenweber’s Restaurant a bit later that year.[16] This means Sawyer was working with African-American musicians before Vernon Castle hired Jim Europe’s band in late 1913. However, this muddles my desire to attribute her collaborations with black bands to Jarrott, who’d performed with African-American musicians back in his Chicago days. Despite this, I do think it’s possible that the reason she hired Dan Kildare, then president of the Clef Club, to form Joan Sawyer’s Persian Garden Orchestra, was both because she and Gilder wanted to rival the Castles, and because Jack had some sway in the decision-making.

The following months were a whirlwind of work accompanied by an avalanche of publicity. The professional team was making between $1,000 and $1,250 a week for their vaudeville engagements at the Palace and other major houses while also dancing at the Persian Garden. Newspapers were full of descriptions of their routines, like the “Three-In-One” featuring the “Jarrott Step,” as well as Jack’s reworkings of the tango, the Maxixe, and other popular dances. Sawyer even claimed they invented the fox trot.[17] However, a frostiness was settling into their personal relationship (never intimate), and on April 13th he walked out on her at the Colonial Theater, agreeing to honour their vaudeville bookings but severing his ties to the Persian Garden. The reason, on top of what Variety reported as “a coldness having existed between Sawyer and Jarrott for some time,” was that Sawyer had apparently been rehearsing with another dancer – not surprising given how quickly she went through partners. It’s reasonable to hypothesize that Joan’s need to be the star at all times was threatened by Jack’s popularity (the four months they danced together was the longest she stayed with one partner and would be surpassed only by the six months with Valentino, always given much smaller billing). Tellingly, in the books published that year to cash in on the dance craze, all glowed when talking of Sawyer and her “refinement,” but Jarrott was relegated to just the photo captions.[18]

Meanwhile, Jack was having problems at home: Gertrude/Josephine claimed to have “heard things about him” when she returned from London in late March, though as I mentioned above, putting her mother’s address on the passenger manifest doesn’t exactly connote confidence in the marriage. Clearly restless, she went to visit friends in Hot Springs and on her return, “kind friends told her some more,” in the winking words of Variety’s reporter. Jack denied whatever it was his wife accused him of doing, but the split was permanent.[19] I’ve yet to locate the divorce papers, but they were surely filed around this time.

While he and Sawyer frostily played out their remaining engagements, Gilder negotiated a movie contract for her protégée with the Shubert Film Company. It was to be Joan’s life story, written by Gilder, “from the days she danced in the chorus to the present time, when she is the manager of her own dance place. The culmination of the play will be the scene in her Persian Garden, showing her exhibition dances, together with the dances of the guests.” The mind boggles: which incidents would be covered? Her assignations with Filipino servicemen in St. Louis? Her mercenary affair with Byron Chandler and the subsequent lawsuit? Her relationship with Gilder? Sawyer went into rehearsals, but sadly the film was never made, and Gilder died in January 1916.[20]

Joan and Jack were back together professionally for a few weeks towards the end of 1915 (she insisted he receive smaller billing), and then there was talk they were teaming up in the summer of 1924, but by that time Jarrott was struggling to stay clean and Sawyer was already 44 years old; if the act really was revived, it played very briefly in only small-time houses. From reviews, it does seem that Joan was at her best with Jack – when she duplicated some of their numbers with other dancers, they didn’t go over in the same way. Maybe she just felt more comfortable with more formal dances like the waltz and minuet, though in the fall of 1914 she took lessons from the leading African-American dance master of the time, Charles Anderson, who also taught the Castles.[21]

She remained a major name for several more years, dressed by Lucile, expounding on theories of dance and colour à la Loïe Fuller,[22] and performing in chic cabarets and vaudeville houses. Restauranteur Joseph Pani (who later married Jack’s dance partner Louise Alexander) claimed that Rudolph Valentino was working for him as a busboy at the Woodmansten Inn in 1915 when Sawyer took him on as her dance partner,[23] but the year doesn’t quite fit since her professional partnership with “Signor Rudolph” didn’t begin until 1916. It was while they were dancing together in the summer of 1916, during her affair with John de Saulles, that William Fox signed Joan to star in her only feature, Love’s Law, a gypsy story directed by Tefft Johnson and released in March 1917. It was not a happy production: shortly after the shoot was finished, Fox realized they had a turkey. Johnson claimed Sawyer couldn’t act and he resigned from Fox, suing for breach of contract and damages of $2,975; the film (presumed lost) opened and closed without much notice, and the case was finally settled in Johnson’s favour in late 1918.[24]

With the dance craze fading and her professional engagements on the decline (she briefly performed in Paris at Claridge’s Hotel in late 1919[25]), Joan did what one would expect: she married a wealthy industrialist. As Mrs. George A. Rentschler she kept busy for a bit, moving between their Ohio, New York and Miami Beach homes, but then in 1929 she got hit with a $100,000 alienation of affection suit by a man named Paul Wiegand, who alleged that Sawyer made his wife Martha dissatisfied in her marriage by her “enticements, favors and seductive influence.” Wiegand appears to have been a thoroughly noxious character, but the stories of Joan taking Martha on long trips and buying her clothes helped his case, which dragged on until the following year and must have been a major source of embarrassment for the Rentschlers.[26] Whatever the state of affairs was between Sawyer and her husband, their union somehow managed to linger on until early 1936 – maybe she just wasn’t willing to give up their yacht – when the divorce was finalized and George remarried at the end of the year (strangely none of the wedding reports even mention that he’d been married previously).

In the ensuing years her name would occasionally pop up in the news, such as in 1944 when she became the bride of J. Gerald Kiley, an adventurer, newspaperman and author who claimed to have written the dialogue for All Quiet on the Western Front (really? Wasn’t that Maxwell Anderson?) and at one time was involved in trafficking monkey glands (no, I’m not making this up). Kiley and Sawyer met years before, probably back in 1919 when she was in Paris and he was known as the “Shimmy King of Paris,” the “Fox Trot King,” and the “Roi de la Danse,” running cabarets after a stint as an ambulance driver during the War. Unsurprisingly, the marriage only lasted four months before Sawyer filed divorce papers.[27]

It’s a great shame Joan never wrote her memoirs, but even if she had, how much truth would she have allowed onto the pages? In later years, while looking at the ocean from the windows of her exclusive Miami Beach apartment, surely she must have thought: “Bessie Josephine Morrison, you’ve done damn well for yourself.” She died at the age of 86, in 1966.

In the next post, I’ll take Jack Jarrott from 1914 until his heart-rending death in 1938.

Jay

Big thanks for help with this post go to Mark Swartz and the Shubert Archive, and Sally Sommer.

[1] Ship manifest accessed from ancestry.com

[2] Howard Rye, Tim Brooks, “Visiting Fireman 16: Dan Kildare,” Storyville 1996-97 (Chigwell, Essex, England: L. Wright, 1997), pp 32-36, 54-55; Tim Brooks, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005), pp. 302-320.

[3] Marriage certificate, October 27, 1902, Toronto, Canada, accessed from ancestry.com

[4] “Says Spouse Met Soldier at Dance,” The St. Louis Republic, November 3, 1905, p. 14; “Filipino Causes Another Divorce,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 18, 1905, p. 13; “Enamored of Filipinos,” Los Angeles Daily Times, December 19, 1905, Part II, p. 1; “Former El Paso Couple Are Divorced in St. Louis,” El Paso Herald, December 23, 1905, Part Two, p. 1.

[5] “Miss Walker a High-Flyer,” Charlotte Daily Observer, July 29, 1906, p. 1; “Lola Walker Makes Denial,” Nashville Banner, August 4, 1906, p. 2; “Chorus Girl Wins,” The Pittsburg Press, August 8, 1906, p. 2.

[6] “Chandler Sued for $100,000,” The Boston Daily Globe, September 1, 1908, p. 1; “Joan Sawyer Wants $100,000,” The Sun [New York], September 1, 1908, p. 10; “‛Boy Millionaire’ Quizzes His Actress,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 6, 1908, p. 14; “$100,000 Suit Dismissed,” The Boston Daily Globe, November 28, 1908, p. 1; “End of Playboy Chandler’s $2,000,000 Spree,” The American Weekly, January 31, 1943, p. 9.

[7] “Wealthy Admirer and Tango Dancer Both Missing,” The New York Herald, February 25, 1912, p. 1; “Maurice is Consoled,” The New York Herald, February 28, 1912, p. 20; “Hurry from the Opera to Start for Europe,” The New York Herald, February 28, 1912, p. 6; “All Narragansett Goes to Casino to See Cabaret,” The New York Herald, July 27, 1912, p. 10; J.C.G. “Narragansett Catches the Cabaret Craze,” The New York Press, August 11, 1912, p. 5.

[8] “Everybody Who is Anybody Goes to Reisenweber’s,” The San Francisco Sunday Examiner, December 29, 1912, City Life Section, p. 2; “Dancers are Fashionable; Go from Fad to Craze,” Variety, December 19, 1913, p. 5.

[9] “Motion Picture Dancing Lessons,” Kalem Kalendar, October 15, 1913, pp. 10-11; “Dancing Lessons Pictured,” The Moving Picture World, October 18, 1913, p. 248. The article mistakenly reports that McCutcheon and Sawyer were dancing in the Ziegfeld Follies. Advertisement, The Moving Picture World, October 18, 1913, p. 331; “Moving Pictures to Teach the Tango,” The Times Dispatch [Richmond, VA], October 26, 1913, Feature section, p. 2; “Kalem’s Dancing Lessons in Great Demand,” El Paso Herald, November 9, 1913, Church and Feature Section; Herbert Reynolds, “Aural Gratification with Kalem Films: A Case History of Music, Lectures and Sound Effects, 1907-1917,” Film History, Vol. 12, No. 4 (2000), pp. 427-28; 433; 441-42. Reynolds suggests the film may have been directed by Robert Vignola. Kristina Köhler, “Moving the Spectator, Dancing with the Screen. Early Dance Instruction Films and Reconfigurations of Film Spectatorship in the 1910s,” in Marina Dahlquist, Doron Galili, Jan Olsson, Valentine Robert, eds., Corporeality in Early Cinema: Viscera, Skin, and Physical Form (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018), pp. 276-78.

[10] “International Book Society,” The St. Paul Globe, September 13, 1902, p. 7. See also “Bachelor Girls,” The Boston Sunday Globe, January 7, 1894, p. 29, which heralds, “Jeannette Gilder and Elsie de Wolfe Are Types of a Unique Class”; Anna Marble, “Women are Successful in Business of the Theater,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 27, 1901, p. 11. For a more recent mention, see Alfred Allan Lewis, Ladies and Not-So-Gentle Women. Elisabeth Marbury, Anne Morgan, Elsie de Wolfe, Anne Vanderbilt and Their Times (New York: Penguin, 2001), pp. 35-36. It’s also worth reading Gilder’s own article about Marbury and de Wolfe: Jeannette L. Gilder, “Elsie de Wolfe’s Art in House Decorating,” Buffalo Sunday Morning News, October 26, 1913, pp. 11, 14.

[11] Miss Sawyer’s Bosworth,” The Washington Post, March 26, 1916, p. 13.

[12] Gavin Lambert, Nazimova: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), p. 129.

[13] “News of the Cabarets,” Variety, October 17, 1913, p. 23; “Chicago Makes High Bid for ‘Society Dancer’,” Variety, December 5, 1913, p. 7.

[14] New York Review, March 7, 1914, quoted in Lewis A. Erenberg, Steppin’ Out. New York Nightlife and the Transformation of American Culture, 1890-1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), p. 162; “Vaudeville News. Keith’s Palace,” The Stage, March 12, 1914, p. 28.

[15] “Cabarets”, Variety, February 13, 1914, p. 20.

[16] Brooks (2005), pp. 270, 329-330; Peter M. Lefferts, “Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn. Materials for a Biography,” Faculty Publications: School of Music. 64, University of Nebraska – Lincoln, 2016.

[17] “Joan Sawyer Tells of Creating Fox Trot,” The Evening Sun [Baltimore], February 16, 1915, p. 5; Joan Sawyer, How to Dance the Fox Trot by Joan Sawyer, Originator of This Season’s Most Popular Dance (New York: Columbia Gramophone Company, 1914).

[18] J.S. Hopkins, The Tango and Other Up-To-Date Dances. A Practical Guide to All the Latest Dances. Tango, One Step, Innovation, Hesitation, etc. Described Step by Step (Chicago: The Saalfield Publishing Company, 1914); Ethel L. Urlin, Dancing. Ancient and Modern (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1914), p. 184.

[19] “Joan Sawyer, Road Attraction,” Variety, April 17, 1914, p. 5.

[20] “Joan Sawyer in Film Play,” New York Tribune, April 26, 1914, section III; “Jeannette Gilder Writes for Joan Sawyer,” The Moving Picture World, May 9, 1914, p. 797.

[21] “Joan Sawyer Comes Back to Broadway,” The New York Press, October 6, 1914, p. 5; “To Hold Dancing Contest at Lafayette Theatre Friday Evening,” The New York Age, October 29, 1914, p. 6; N. H. Jefferson, “Latest New York News,” The Chicago Defender, December 5, 1914, p. 7. For the most recent scholarly discussion of Anderson’s crucial place in dance history, see Danielle Robinson, Modern Moves: Dancing Race during the Ragtime and Jazz Eras (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[22] “Joan Sawyer’s New Ideas,” The New York Times, July 5, 1914, Section X, p. 7. It seems she never put into practice these ideas.

[23] Lucius Beebe, “Out of the Legendary Past,” The Everyday Magazine in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 24, 1939, p. 5; “Obituary,” The Daily News, March 7, 1942, p. 20.

[24] “Joan Sawyer at Work,” Variety, August 25, 1916, p. 27; “Two Fox Directors Out,” The New York Clipper, November 8, 1916, p. 32; “Suit Against Fox,” The Billboard, December 30, 1916, p. 6; “Fox-Johnson Case Settled,” Variety, November 29, 1918, p. 44; “Johnson’s Claim Against Fox Settled,” Variety, December 6, 1918, p. 42.

[25] “Informations. Au Claridge’s Hôtel,” Le Figaro, December 8, 1919, p. 3.

[26] “Steel Man Loses Wife’s Love, Sues Woman Dancer,” The St. Louis Star, November 27, 1929, p. 3; “The Wiegand Divorce Suit Heard,” Hamilton Daily News, May 14, 1930, p. 3.

[27] “J.G. Kiley, Miamian Wed Today,” Miami Daily News, February 29, 1944, p. 4-A; “Author Predicts Risque Plays,” Miami Daily News, March 24, 1935, Second Section, p. 9; “Kaiser Considering Monkey Gland Operation, Says Report in Paris,” Daily News [New York], October 23, 1922, p. 18; Swing, “Chicago by Day,” Variety, August 15, 1919, p. 17; “Several Thousand Doughboys Seeking Fortunes in France,” The Sun [Baltimore], November 23, 1919, p. 4; “‛Les Deux Masques’, dancing américain,” Paris-Midi, November 30, 1923, p. 1; “Re-Enter Jed Kiley,” Jazz. A Flippant Magazine, January 1, 1925, pp. 10-11; “Mrs. Kiley Sues for Divorce,” The Miami Herald, June 17, 1944, Section B, p. 1. Someone has to look more into this extraordinary man’s life.

English

English

Commenti recenti