EL ÚLTIMO MALÓN

[The Last Uprising]

Alcides Greca (AR 1918)

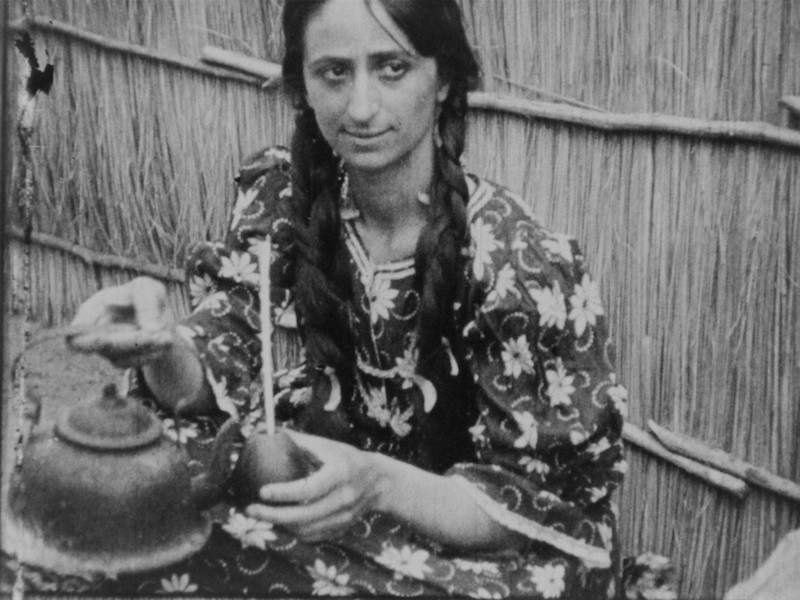

On 21 April 1904, after decades of repression, members of the Mocoví tribe attacked the white population of San Javier, in the northeastern Santa Fe province of Argentina. The uprising, or “malón”, was violently put down, and more than fifty indigenous people were slaughtered. Thirteen years later, the local writer and politician Alcides Greca (1889-1956) brought together a group of survivors to participate in a filmed re-enactment. The result was El último malón, an exceptional film that not only carefully reconstructs the massacre, but also illustrated now vanished Mocoví customs.

Greca’s idea for his first and only film was to show the causes of the uprising: no romance, no fiction, just the facts via a precise reconstruction of events. As he explains in an introductory handwritten intertitle, “It will not be the sickly boulevard poetry imported from Paris, nor a melodramatic novel. It will be the true story of a heroic and strong American race in the jungle of Chaco…”. However, compromises were made once the owner of the Cinematográfica Rosarina film lab and production company urged him to introduce a love story to the plot: “the audience will appreciate this, otherwise you will lose all the money invested.” This explains the presence of Rosa Volpe (one of only two professional actors in the film) as Rosa Paiquí, the woman fought over by the chief Bernardo López and his rebel brother Jesus Salvador. In reality, López was the Mocoví cacique, or headman, adding a crucial layer of verisimilitude to the two intertwined stories, part romance, part historical reconstruction (“Art and reality,” as we read in one advertisement), that tie in with nascent documentaire romancé ideas just being discussed in Europe, with their mixture of travelogue and fictional stories set in exotic places that feature white actors supported by indigenous-looking extras.

However, El último malón subverts the unwritten rules of the documentaire romancé because it’s less a romance than a rigorous document. It’s important to underline that the entire story is told from the indigenous point of view, something very unusual in the period, with the Mocoví as the undisputed protagonists while the whites are just extras, thus challenging the usual documentaire romancé formula, as was the case with its immediate precedent, Edward Curtis’s In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914). A later reference point for El último malón is of course Nanook of the North (1922), which has led Fernando Martín Peña to suggest in his 2015 book Cien años de cine argentino, “if it was an American film it would be considered the predecessor of Robert Flaherty and would have an important place in the history of cinema.”

Countering the racist canard of the indigenous population as savages, Greca makes a point of showing the complex ideological and political positions within the community that ultimately resulted in the uprising. Though the parallel fictional fraternal rivalry and love story adds dramatic interest, the film avoids the merely picturesque and doesn’t undermine the strength of the political denunciation that is the purpose of the whole narrative. Greca, also acting as producer, gave great importance to every detail, including the title designs by renowned architect and artist Ángel Guido. The Mocoví allowed the filmmaker full access to their daily lives in the village, their laborious work on the estancias (ranches) and yacare caiman hunting, which, unlike the fictive methods in Nanook, really were done in the traditional way without firearms. Everything shown of Mocoví life beyond the expressive elements inherent with anything being filmed is as close to reality as possible, and the Mocoví universe that appears before Greca’s camera continued in a similar fashion for some time after shooting was completed.

El último malón premiered in Rosario, the largest city in Santa Fe province, and was enough of a success that Greca brought it to Buenos Aires three months later, accompanied by several Mocoví as publicity magnets. It received good reviews in the papers, but the public turned their backs on the film, which soon fell into oblivion, and Greca retired from cinema. By 1956, two 35mm tinted nitrate prints were known to exist, but in 1968, faced with their advanced state of deterioration, the Cine Club Rosario made a 16mm black & white internegative and print from one of the copies, now housed at the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, where in 2009 Fernando Martín Peña and Paula Félix-Didier rescued the film for the second time. Following notes taken by film collector Octavio Fabiano and film critic Jorge Miguel Couselo, who had examined the originals, they digitally reproduced some of the colors and reconstructed some intertitles. The new 4K version follows this work; one complete scene has been digitally reconstructed, while the lost original title was replaced with a still. The other nitrate print remains lost.

Andrés Levinson

regia/dir, scen: Alcides Greca.

did./title des: Ángel Guido.

cast: Mariano/Bernardo López (capo dei Mocoví/chief of the Mocoví), Jesus Salvador López (leader dei ribelli/Mocoví rebel leader), Rosa Volpe (Rosa Paiquí), Alcides Greca (se stesso/himself), Fernando Centeno (se stesso/himself), Juan Luis Ferrarotti (se stesso/himself), sopravvissuti dell’insurrezione del 1904/survivors from the 1904 Mocoví uprising.

prod: Greca Films.

riprese/filmed: 1917.

uscita/rel: 04.04.1918 (Palace Theatre, Rosario City).

copia/copy: DCP, 71′ (4K, da/from 16mm, 18 fps, orig. c.70′); did./titles: SPA, subt. ENG.

fonte/source: Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducrós Hicken, Buenos Aires.