OBLOMOK IMPERII

(Fragment of an Empire)

Fridrikh Ermler (USSR 1929)

Original score by: Vladimir Deshevov

Performed live by: Orchestra San Marco, Pordenone

Conductor: Günter A. Buchwald

Fragment of an Empire is one of the most canonical works of Soviet silent cinema (it was in fact shown at the Giornate in 2011 as a part of the Canon Revisited series). It is considered Fridrikh Ermler’s key work, and features a legendary performance by Fiodor Nikitin. The sequence in which the main character’s memory returns is often described as a perfect blend of Soviet montage and Method acting. But, as it turned out, for decades we were dealing with a re-edited and abridged version. Even the most famous shot of the film, that of Christ in a gas mask, reproduced in dozens of publications, was absent from all the distribution prints.

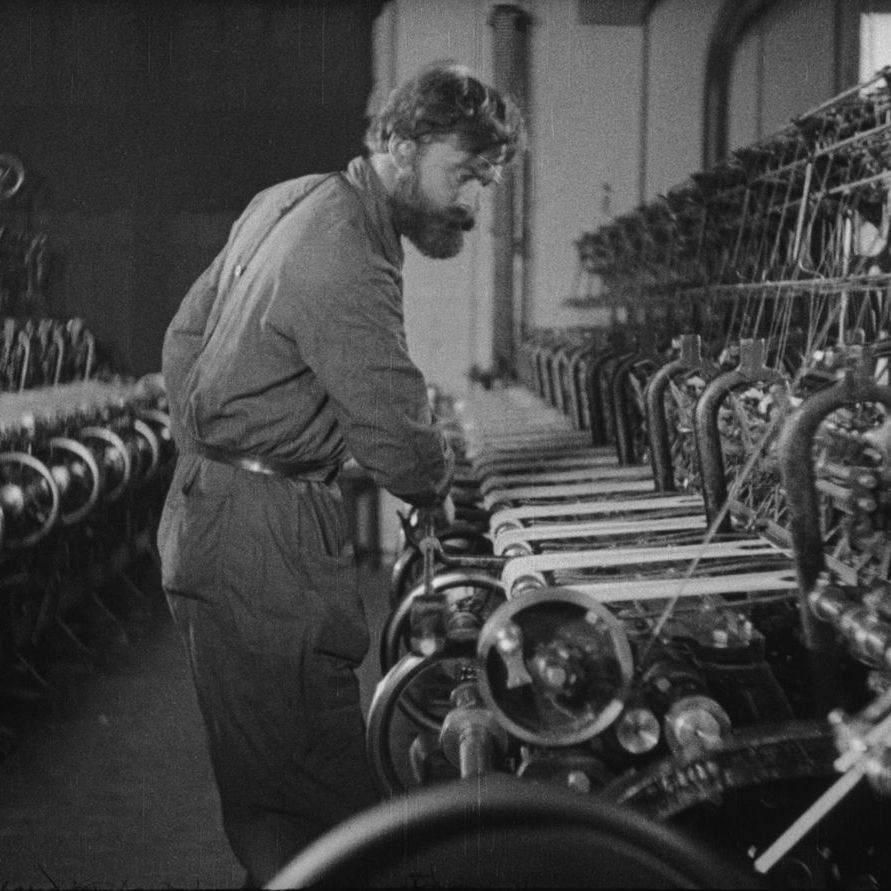

The film tells the story of Filimonov, a non-commissioned officer who has lost his memory because of shell-shock during WWI and who “awakens” ten years later. He finds himself in an unknown city (Leningrad, instead of St. Petersburg) in a new country (the USSR, instead of Russia), the factories now belong to “the people” (whatever that means), and Filimonov’s wife has a new husband.

Ermler’s intentions were to show the renewal of the country, the accomplishments of Soviet power, and the liberation and rebirth of the people, all through the eyes of a newcomer. But he had a remarkable ability to let the cat out of the bag, to turn propaganda into the most unvarnished exposure of reality. This happened exactly because he was a “Party Artist” and active Communist: Ermler sincerely believed that if everything happening in the country was not necessarily good, it was nonetheless expedient. And thus there was no sense in distorting or decorating reality.

In Fragment, a man who used to have a world of his own, a house, a wife, finds himself surrounded by faceless members of the Komsomol, in a land of Constructivist blocks which press down on him from all sides. “Where is Petersburg? Who is the master here?” he screams hysterically. But there is no Petersburg any more. There is a new, frightful city-hybrid (part of the film was shot in Kharkov, because there was still relatively little Constructivism on view in Leningrad). And there isn’t a master – only the factory committee. “Poor fellow, he is to learn,” wrote Oswell Blakeston in Close Up in January 1930. “His marvellous face moves through a thousand positions, as quickly as the streets which flash by him from the tram cars. An arch is almost a halo round his head. But the new architecture terrifies him; he runs away. (…) the influence of the revolution (…) has changed the lovely Eisenstein type to the proletarian Menjou. (…) Victory. A new man. Yes, but something else has died.”

The famous scene of the protagonist regaining his memory was made under the definite influence of Freud (of whom Ermler was a huge admirer). Its climax was a succession of crosses – a military cross, a cross on a church, a cross at the cemetery. Concluding with a big Crucifix somewhere on the battlefield, and on Christ’s face, a gas mask (which was a citation of a scandalous anti-military drawing by George Grosz, one of the leading graphic artists of German Expressionism and the Neue Sachlichkeit/“New Objectivity”). Fragment of an Empire was widely distributed at the time of its original release, and each country had a censorship of its own. But of the nine versions (and a couple of dozen prints) that were located during this restoration, only two contained the Christ image.

Numerous public screenings of Fragment in its native country in 1929-1930 proved that both its language and the multi-layered narrative were too complicated for the “masses”. It was decided to make a simplified version of the film – mainly for distribution in the villages. It now appears that what was long known as the “canonical” version of Ermler’s masterpiece is in fact this “village adaptation”.

But it’s not only the missing shots and scenes that called for a new restoration. The original intertitles, which we are able to see for the first time since the 1930s, are not just remarks and lines of dialogue, but a full-fledged element of montage. They change in size and even in geometrical form, which is not only visually impressive, but determines the intonation. Finally, for the first time, this film has been restored using original nitrate prints; the previous restorations were based on a post-war dupe negative.

All his life Ermler was highly receptive to music, and his career is marked by fruitful collaborations with some of the leading Soviet composers, including Dmitri Shostakovich and Gavriil Popov. The first of these was with Vladimir Deshevov (1889-1955), an eminent composer of the Russian avant-garde. Fragment of an Empire was one of the very few Soviet silent films with a commissioned orchestral score. However, Deshevov’s music was rarely performed – perhaps because it was anything but optimistic, and emphasized the ambiguity of the film’s ideology: tragedy here is mixed with sarcasm. Whether Ermler realized that or not, he was fascinated by Deshevov’s work, and wrote to him: “I am afraid that people will go to listen to the music, not to watch the film. So be it! I am delighted.”

This restoration was based primarily on a 35mm nitrate print held at the Eye Filmmuseum, supplemented with another nitrate from the Cinémathèque suisse (which contained not only the legendary Christ-with-gas-mask image, but the original Russian intertitles for Acts 2-6 as well). The continuity was checked, and the titles absent from the Swiss print have been reproduced based on the Russian “montage lists” (censorship records) held at Gosfilmofond.

The music

All his life Ermler was highly receptive to music, and his career is marked by fruitful collaborations with some of the leading Soviet composers, including Dmitri Shostakovich and Gavriil Popov. The first of these was with Vladimir Deshevov (1889-1955), an eminent composer of the Russian avant-garde. In the mid-1920s he was as big a name as Shostakovich or Prokofiev (during his visit to the Soviet Union, Darius Milhaud was more impressed by Deshevov than by any other Soviet composer, calling him a “real genius”).

Fragment of an Empire was one of the very few Soviet silent films with a commissioned orchestral score. There were half-a-dozen pictures in the mid-1920s with compilation scores (and the films themselves were on the traditional-commercial side). But the Leningrad Sovkino factory launched a new trend in 1929, right before the advent of sound.

The idea belonged to Adrian Piotrovsky (1898-1937). A true Renaissance man, Piotrovsky was a dramatist, a translator from ancient languages (his translations of Aristophanes, Aeschylus, Catullus, Plautus, and Petronius are considered absolutely canonical), a literary scholar, a highly influential critic, and the godfather of several experimental theatres; these were just a few of his protean talents. As the literary director at the Maly Opera Theatre in Leningrad (acronym MALEGOT), he played a crucial role in introducing new avant-garde music to Soviet audiences – such as Alban Berg’s Wozzeck and Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. He also wrote librettos for Shostakovich’s The Limpid Stream and Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet. From 1928 to 1937 he was formally the head of the Script Department at the Leningrad Sovkino factory (later known as Lenfilm); in reality, Piotrovsky was the brain and soul of the company, essentially its creative director. It was his idea to engage some of the leading Soviet composers to write original scores for silent film. Besides Deshevov’s score for Fragment of an Empire, only three others are known to have been completed: Shostakovich’s score for The New Babylon (1929) by Grigorii Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg is the most famous; Dmitrii Astradantsev’s scores for Yevgenii Cherviakov’s The Golden Beak (1929) and The Sleeping Beauty (1930) by the Vasiliev Brothers are never performed, since the first film is lost and the second exists only in fragments.

Deshevov’s music for Fragment of an Empire was practically ignored by the press of the time (though the few existing mentions are positive) – perhaps because it was anything but optimistic, and emphasized the ambiguity of the film’s ideology: tragedy is mixed with sarcasm. Did Ermler realize this? Who knows? But he was fascinated by Deshevov’s work, and praised his music exactly for its “colossal social impact and raising the film to a new level”. “I never thought that music could make such a difference to a film,” he admitted, writing to the composer: “I am afraid that people will go to listen to the music, not to watch the film. So be it! I am delighted.”

Deshevov’s score was written for the original version of the film. In the 1960s and early 2010s there were several attempts to match it with the “village version”, but only now can we appreciate it in its original format.

Peter Bagrov

regia/dir: Fridrikh Ermler.

scen: Katerina Vinogradskaya, Fridrikh Ermler, da un’idea di/based on an idea by Katerina Vinogradskaya.

photog: Yevgenii Shneider; asst. Yakov Svetitskii;

esterni/exteriors: Yevgenii Mikhailov;

cam. op. (2nd unit): Gleb Bushtuev.

scg/des: Yevgenii Yenei.

asst dir: Robert Maiman, Viktor Portnov.

mus: Vladimir Deshevov.

prod. mgr: Adolf Minkin.

cast: Fiodor Nikitin (sottufficiale Filimonov/Filimonov, non-commissioned officer), Liudmila Semionova (sua moglie/his wife), Valerii Solovtsov (suo marito, un operatore culturale/her husband, a cultural worker), Yakov Gudkin (soldato dell’Armata Rossa ferito/wounded Red Army soldier), Viacheslav Viskovskii (ex proprietario della fabbrica/former owner of the factory), Lidia Ulman (sua moglie/his wife), Sergei Gerasimov (ufficiale zarista/White officer), Ursula Krug (superiore di Filimonov alla stazione/Filimonov’s employer at the station), Vladimir Stukachenko (l’operaio che dà istruzioni a Filimonov/worker instructing Filimonov), Viktor Portnov (ubriacone/drunkard), Sergei Ponachevnyi (comandante dell’Armata Rossa/Red commander), Boris Feodosiev (ufficiale/officer), Emil Gal (passeggero sul treno/passenger on train), Varvara Miasnikova (controllore/tram conductor), Bella Chernova (signora sul tram/lady in a tram), Yuri Muzykant (uomo sul tram/man in a tram), Piotr Savin (un tizio in fabbrica/guy at the factory), Aleksandr Melnikov (giovane operaio/young factory worker), Vera Bakun (ragazza al bar/girl in the canteen), Rasma Mashkevich.

prod: Sovkino (Leningrad).

uscita/rel: 28.10.1929.

copia/copy: 35mm, 2239 m. [2218 m. + 21 m. restoration credits] (orig. 2203 m.), 109′ (18 fps); did./titles: RUS.

fonte/source: San Francisco Silent Film Festival.

Restauro/Restored 2018: EYE Filmmuseum, Gosfilmofond of Russia, San Francisco Silent Film Festival; collab: Cinémathèque suisse; restauro/restoration: Peter Bagrov, Robert Byrne, Annike Kross; a cura di/curated by: Elif Rongen-Kaynakçi.